Table of Contents

Canvas is the learning management system used here at DSU for online classes. Some of your in-person classes will use it too. LIB 1010 is entirely online and Canvas will be the online tool you will use to participate in the course and access all its content. This chapter will help begin to orient you to the Canvas interface so you will begin to learn the basics of using Canvas.

Once you are in Canvas, you will be working through the course using a series of weekly modules. These modules are accessed by clicking on the “Modules” button in the left navigation menu of the course. Please visit this link to find instructions on editing your profile and preferred e-mail settings.

For more information using the features of Canvas, or if you need further assistance visit this link.

Librarians are experts in finding information, we’re here to help and there are many convenient ways to contact us. Don’t be frustrated; librarians are here to help you. Contact us.

According to the Association of American Colleges and Universities (AAC&U), an information literate individual is able to:

Please view the following video which explains information literacy and how it can benefit you! — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VaWv5S50Zww&list=PLoOfFGEKrndoDxmMGod1qHde4j1mzOwHv

Why is Information Literacy important in the real world, not just for academic use? View this video to find out more. — https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ciSWknQ98o8

Visual literacy is basically the ability to understand, interpret and evaluate visual material and to use them ethically.

The following information was retrieved from a book, called Media Literacy in the K-12 Classroom, by Frank W. Baker.

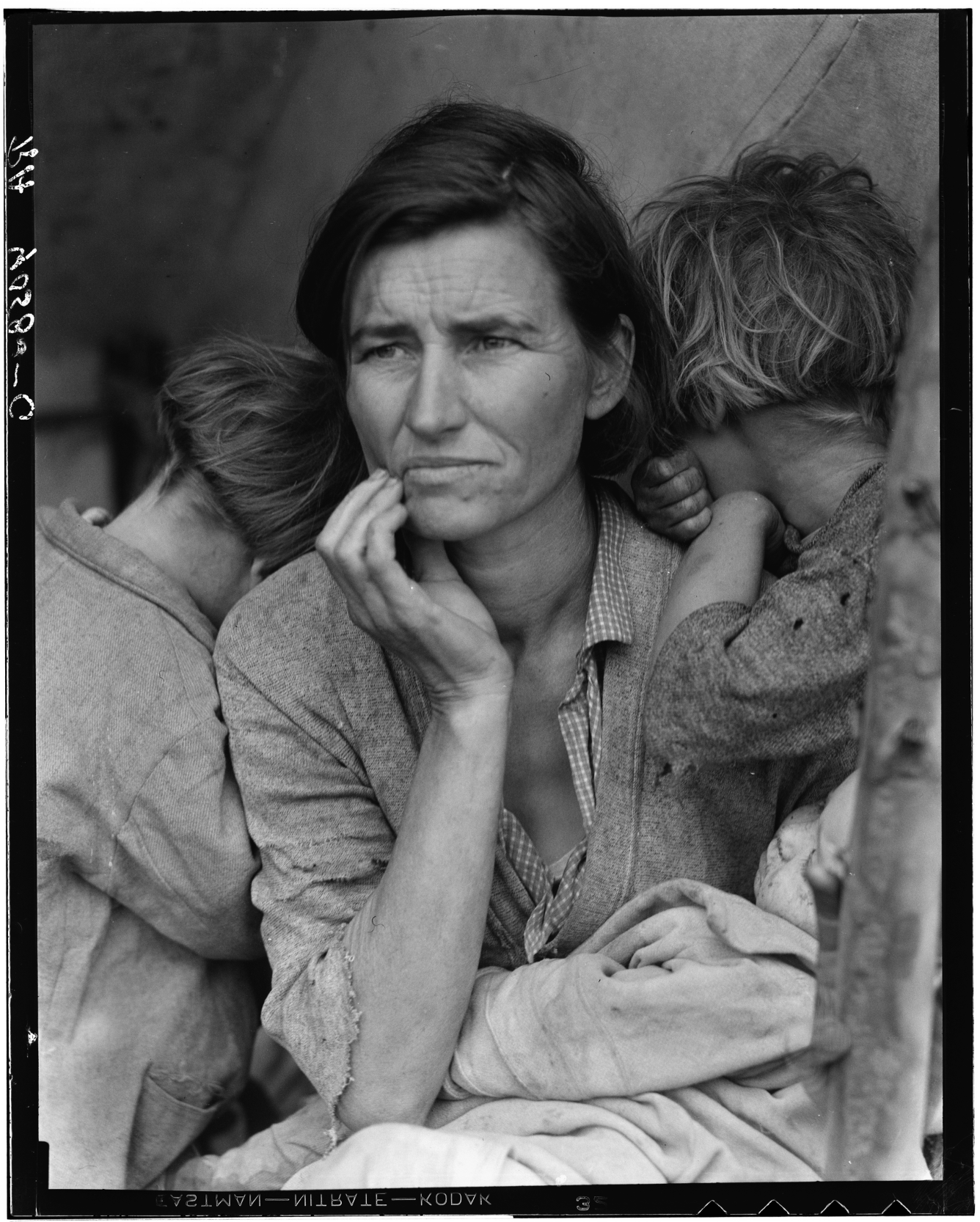

In 1935, photographer Dorothea Lange, while working for the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, snapped a picture of a migrant farm worker and her starving children at a farm in California where the workers were picking peas. Lange was one of a number of photographers who were hired to document conditions of people during the Great Depression. Little did she know that the photo of Florence Owens, known as “Migrant Mother,” and the accompanying news coverage would cause the government to rush food aid to the starving workers.

“Migrant Mother” by Dorothea Lange

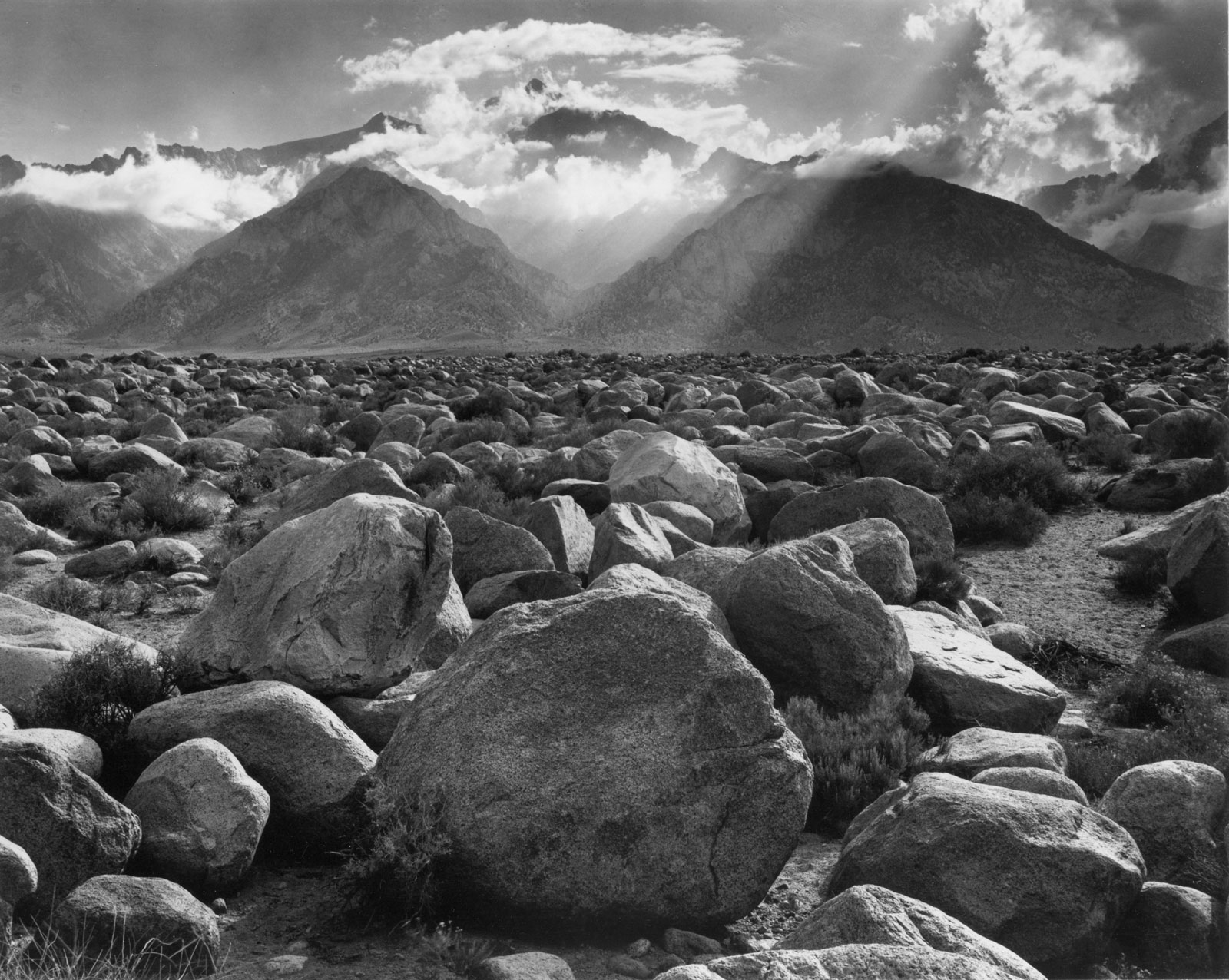

Ansel Adams’ photograph of Mount Williamson. (Copyright held by the Ansel Adams Publishing Rights Trust)

In 1945, when America was still involved in WWII, Ansel Adams photographed Mount Williamson, part of the Sierra Nevada Mountain range in California. It is a beautiful image: clouds sit atop the mountain range, and the sun’s rays find their way through the clouds, past the mountain to the ground below. In the foreground, large rocks can be seen. It’s a nicely balanced photo and represents one of the best landscape photos ever taken. But, might something else be going on here? Media literacy asks us to consider what is outside the frame; what do we not know? Unless you have studied Adams and his images, you would not have known that this vista was the view for the Japanese-Americans who were detained during World War II in an internment camp located at Manzanar, California. The internees were allowed outside only to collect smaller rocks for their gardens. Now that you know this, does it change the way you understand or feel about the photograph?

The first 10 minutes of the 2008 animated feature film WALL-E contain no dialogue. There are no words to describe the action; the audience has to interpret what is happening simply by watching and listening to the action on the screen. The action: we meet WALL-E, the garbage-collecting robot whose sole job is to clean up Earth after it has been abandoned by all humans. See a PowerPoint presentation (www.rickinstrell.co.uk/TeachingWallE.ppt) for more information on how WALL-E communicates to its audience.

Visual literacy is something that has been primarily confined to our arts classrooms; in the arts, students learn how to look at a painting and how to read, analyze, and deconstruct the techniques used by the artist. Usually they study and become aware of concepts such as lighting, color, composition, and more. Today, the need for visual literacy has spread to other disciplines. Because so much information is communicated visually, it is more important than ever that our students learn what it means to be visually literate. Those who create visual images (such as photographs or videos) do so with a purpose in mind, using certain techniques. In order to “read” or analyze an image, the audience (our students) must be able to understand the purpose and recognize the techniques. Just like media literacy, visual literacy is about analyzing and creating messages. Images can be used to influence and persuade, so it is incumbent upon educators to learn how to teach with and about images and to help our students understand the language of photography and video.

Whether they are images in a text or a picture book, news photos in the morning’s newspaper, a digitally altered photo of a fashion model on the cover of a magazine, or a video on YouTube—images are a major part of our world. Most of us now take lots of pictures and videos because our mobile phones include embedded cameras. A recent Pew survey found that 83% of American teens take pictures with their cell phones (Lenhart, Ling, Campbell, & Purcell, 2010). More students are into photography because of its accessibility. The size and affordability of smaller cameras makes incorporating images into instruction easier than ever. There are also a host of photo-sharing websites where we can upload and share our images and videos with others.

As students conduct research and look for information online, they will invariably come across something that appears to be authentic but, upon closer examination, analysis, and questioning, they’ll discover that someone is out to fool them. They’ll find that someone has used specific techniques to make a website, photo, or magazine cover look real—but it is not real. The need to evaluate the sources is imperative. The evaluation tool later discussed to evaluate websites should also be used on videos and photographs when using them to convey a message.

One example is an ad that ran in a Philadelphia newspaper for the new airliner, “Derrie-Air,” which proudly announced that customers could book a seat based solely on their weight. They even created a website, http://flyderrie-air.com which newspaper readers clicked on. A big practical joke, it seems. The airline does not exist, but many unsuspecting news consumers were taken in by this parody.

A fake website for a fake airline

Copyright 2012, ISTE® (International Society for Technology in Education), Media Literacy in the K–2 Classroom, Frank W. Baker.

1.800.336.5191 or 1.541.302.3777 (Int’l), iste@iste.org, www.iste.org. All rights reserved. Distribution and copying of this excerpt is allowed for educational purposes and use with full attribution to ISTE. Modified by Linda Jones, Dixie State University, 2016, Retrieved from http://www.iste.org/docs/excerpts/MEDLIT-excerpt.pdf

| Primary Sources | Secondary Sources | |

Definition |

Related to or being a firsthand account, original data, etc., or based on direct knowledge, as in original source. |

Related to a source that is not original but is based on information found in a primary source |

Explanation |

Primary sources are often required in college level research. Often, the authors of primary sources are the researchers themselves. A primary source is valuable to the researcher because they contain direct evidence about a particular subject that you might be studying. Primary sources can be artifacts like an original piece of music, pottery, photography, furniture, clothing, or architecture. They can be creative works, legislation, raw statistics, some government or organizational documents, personal narratives, correspondence, and journal articles published in peer-reviewed publications, radio recordings, and interviews. Certain newspaper articles reporting events and not offering any analysis or interpretation are primary sources. |

A secondary source is a source that takes information from primary sources and summarizes, analyzes, evaluates, interprets, discusses, and provides commentary on the content of the primary source. Can be written as scholarly periodicals, scholarly books, magazines, newspaper articles, textbooks, works of criticism/interpretation, materials that analyze events or materials that analyze creative works. |

Examples |

Primary sources may have been written during a time period that you might be studying. For example, you might be studying the American Civil War. A diary written by a soldier that fought in the American Civil War would be an excellent example of a primary source you could use in your research. The diary is “primary” because the author who wrote the account personally experienced the events. |

Shakespeare’s plays written in modern English. Newspaper articles where the newspaper person didn’t see the incident but asked an eye witness their story. |

Exceptions |

Some secondary sources can contain primary source material. For example, a history book might contain an analysis about a time period and include stories from eye witnesses. |

You can pick a topic for a research project by using several tools available through the DSU Library website. Subject encyclopedias are a great way to discover a topic. Databases like CQ Researcher or Gale Opposing Viewpoints explore current issues and hot topics. Websites of major news and media outlets like Fox News or CNN explore current issues happening around the world.

The research process often begins with a topic that you are interested in exploring and writing about. When selecting a topic, consider your audience.

Make sure that it fulfills the assignment and can be focused to fit the assignment.

Ask yourself:

Once you establish these specifics, you can begin formulating a research question or series of questions based on that need. Formulating research questions helps you define your topic, identify main concepts, and narrow or broaden the topic. The topic can be developed further throughout the research process. Start with a very broad topic and then conduct an information scan to see if potential resources are available.

Make sure that you have enough information to fulfill the assignment. You need to have enough to answer your research questions or the questions that are assigned by your instructor. A generally accepted rule to follow is to include at least two sources per page of your written work. So if you write a five page paper you should at least have ten sources. Your instructor may specify how many sources you need to have, so be sure to satisfy the assignment requirements.

An Information Scan is a quick look at resources to determine the appropriateness of a topic based on the amount and type of information found. An information scan will also help you determine if there is enough information available to support your topic.

Start by searching the Internet to answer some of the questions below. The Internet should not be the first place to look for actual sources, but it can be useful in choosing a topic. Don’t look for actual sources, ask these questions instead:

For example, in a psychology course, your starting point may be the broad topic of adult psychology. You can begin to narrow to the first level of specificity and decide to explore post-traumatic stress disorder. You can then further refine and narrow this topic as you find more information so as to ensure you will have enough to support your final topic.

Remember to select a topic by working from the broad and general to the specific as you find information. Sometimes it is necessary to narrow the topic further in order to meet the goals of the assignment. Other times you may not find enough information and it can be helpful to broaden the topic if you have started out with something very narrow. You may need to clarify or refine your research questions in your paper by narrowing the focus or broadening the scope. Consider revising the search strategy to include different search terms or additional resources. Be willing to adapt the question to fit the information available.

An efficient technique in research is having the flexibility to adapt or modify your topic based on the information you find. This is a significant benefit when researching at the college level. When you can select your own topic, rather than having one assigned by an instructor, don’t settle on a specific topic until you have gathered your information. Simply revise the topic to narrow or broaden the scope. Before abandoning a topic, reevaluate your original question, and seek advice from an expert. You may be closer to completing your research than you think!

Using the example of post-traumatic stress disorder or PTSD, you may discover that it is commonly associated with war veterans, but there are other really interesting topics as well. Research ideas may emerge from an information scan on PTSD that might include an exploration of terrorism and PTSD based on a geographic region. You might explore PTSD and natural disasters, effects in first responders (exploration of a specific population), or treatments for PTSD induced by terrorism vs. treatment for PTSD which developed after being a victim of natural disaster (compare and contrast this in your paper.)

Using the example of PTSD, some examples of questions you could formulate on this topic might include:

Once you have completed an information scan and have chosen a topic, you can begin developing a Research Plan. One of the most effective plans is this:

One of the questions you addressed in choosing a topic was whether you needed scholarly and/or peer reviewed sources. How can you tell if a source is scholarly or non-scholarly?

| Scholarly Journal Article | Non-scholarly Journal Article | |

| Purpose | To share the results of primary research and experiments with other scholars. | To entertain or inform in a broad, general sense. |

| Audience | Researchers; Academic faculty & students. | The general public. |

| Author | A respected scholar or researcher in the field; an expert on the topic; authors’ names are always noted. | A journalist, feature, or freelance writer; authors’ names not always noted. |

| Publisher | A professional association; a university or scholarly commercial publisher. | A commercial publisher. |

| Appearance | Very basic layout, usually black text on white paper; tables or charts to illustrate research components; advertising is at a minimum and is subject-related. | Often printed on glossy paper with colored text or headlines; usually has accompanying photographs and many advertisements. |

| Publication Acceptance | Experts (peers) in the field review each article submission before publication acceptance (i.e. peer reviewed). | Writers are often employed by the magazine or publisher; acceptance is based largely on the topic’s consumer appeal; not peer reviewed. |

| Language | College-level; specialized vocabulary or jargon of the discipline. | Non-technical, conversational/simple vocabulary. |

| Article Length | Often lengthy (approximately 10-30 pages). | Often short (approximately 1-10 pages). |

| Article Organization and References | Highly-structured; include abstracts, review of literature, methodology, and citations to sources; always contain a bibliography of references. | Loosely-structured; rarely have bibliographies; sometimes informally mention sources. |

| Examples | HarperCollins Publishers, Dutton | Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report, Time |

How can you tell if an article is scholarly by looking at it? Find out by clicking on different sections and learn the anatomy of a scholarly article. http://www.lib.ncsu.edu/tutorials/scholarly-articles/

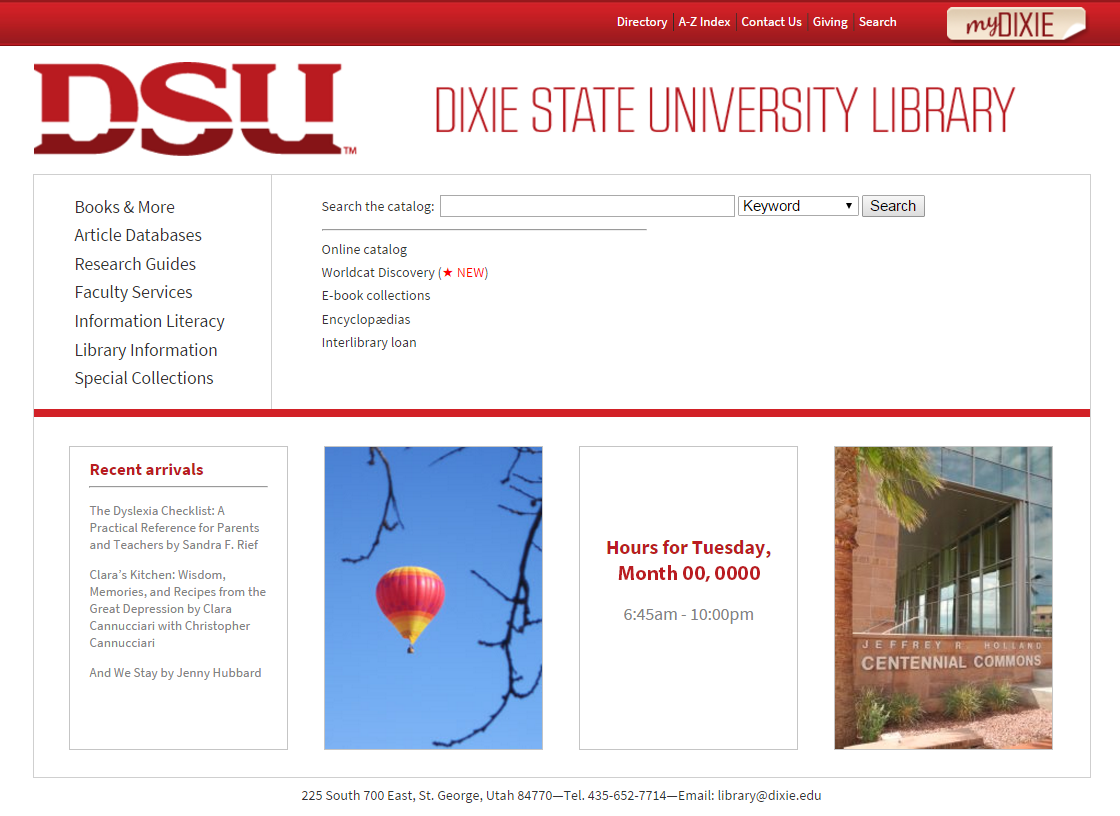

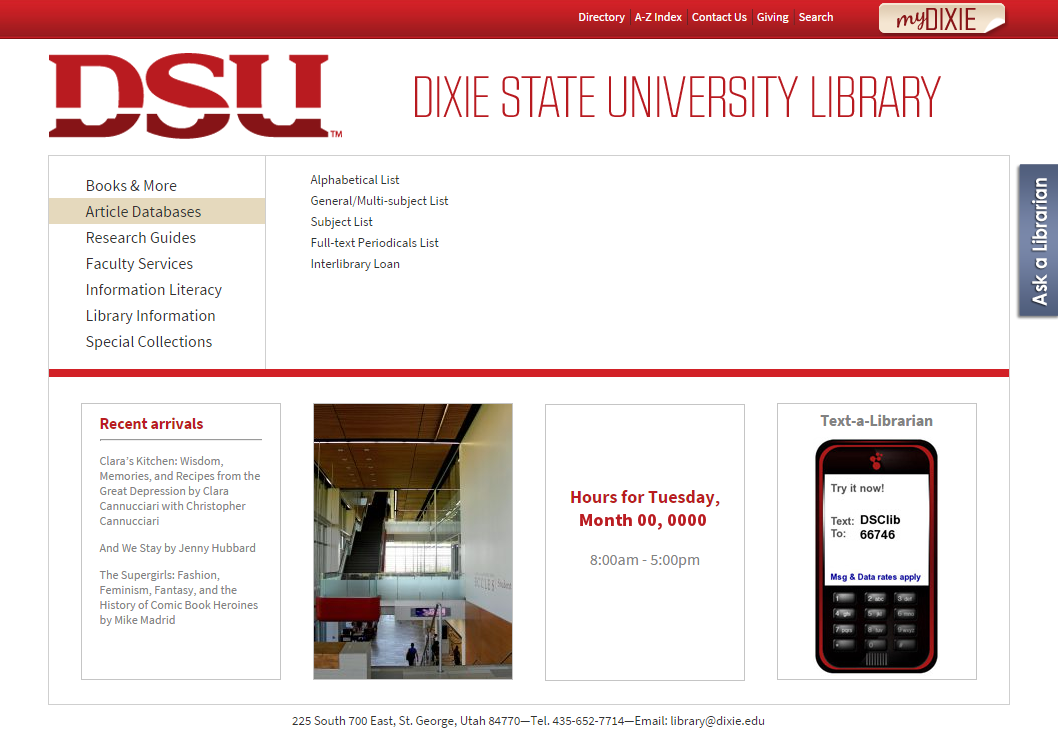

The DSU Library web site can be accessed by visiting library.dixie.edu

Figure 3A: The DSU Library Homepage.

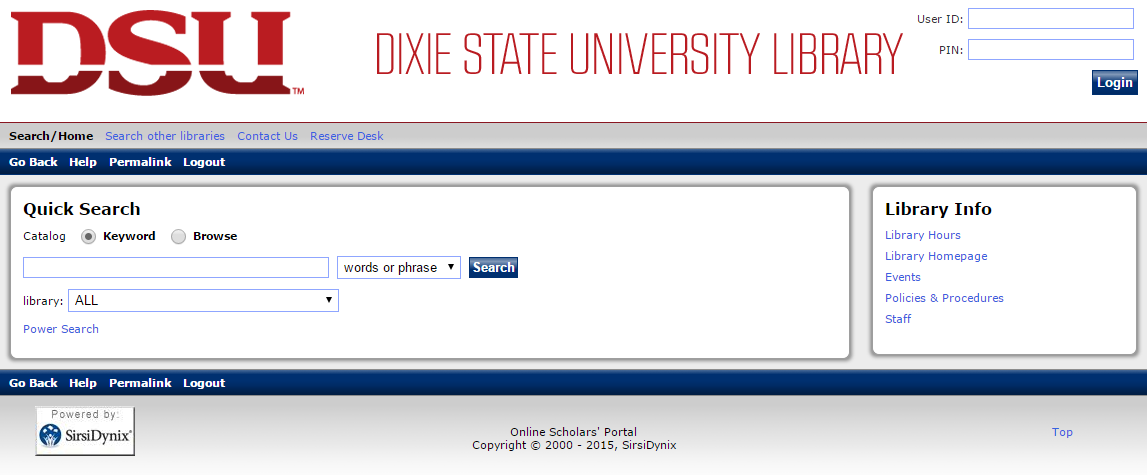

Figure 3B: The DSU Library Online Catalog with the “Quick Search” displayed.

The Online Library Catalog is located in the Books & More section of the library web site (Fig. 3A). The catalog allows you to search all of the library holdings (books, ebooks, encyclopedias, DVDs, CDs, etc.) with the exception of materials held in the Article Databases (articles from periodical sources, etc.)

The Online Library Catalog (Fig. 3B) has basic and power search features, and links to information such as library hours.

The DSU Library has many print and media resources for your use such as books, DVDs, and music CDs. These physical items are housed in the library on the second and third floors of the Holland Centennial Commons Building. Some of these items are rare or need special care and are housed in our Special Collections Library & Archive (on the third floor of the HCC).

These items are searchable using the library catalog (Fig. 3B).

The library has a number of collections, including:

The DSU Library Catalog (Fig. 3A and 3B) gives you access to most of the library materials except those found in the article databases. Here are a few tips to help you find what you need for your research:

Click on “Catalog Record” for more details about an item that you have found. This will show you details like a table of contents and may include clickable links to other items that are closely related to your research subject. These clickable links use Subject Headings. Subject Headings are the Controlled Vocabulary used to organize and describe the items that are in the DSU Library catalog. More details about Controlled Vocabulary are found in the next chapter.

DSU Library Catalog Features:

Each item in the library collection is identified by a Call Number to help retrieve the item in the library. A Call Number is a number generated by a classification system and is unique to each item in the library. It is like an address of where it can be found in the books stacks. This number is displayed in the catalog (Fig. 3B) when you search and is on the item itself. By matching the number from the catalog to the one displayed on the item, you can find the item you are searching for. Some examples of call numbers are:

WorldCat Discovery (Fig. 3A) is a tool that can be used to search the online library catalog and some of the article databases in one interface. In addition to the convenience of searching in one place, WorldCat is a catalog that includes our materials as well as materials from other libraries around the world. Additionally, a search can include sources like the Government Printing Office giving you information on U.S. government publications.

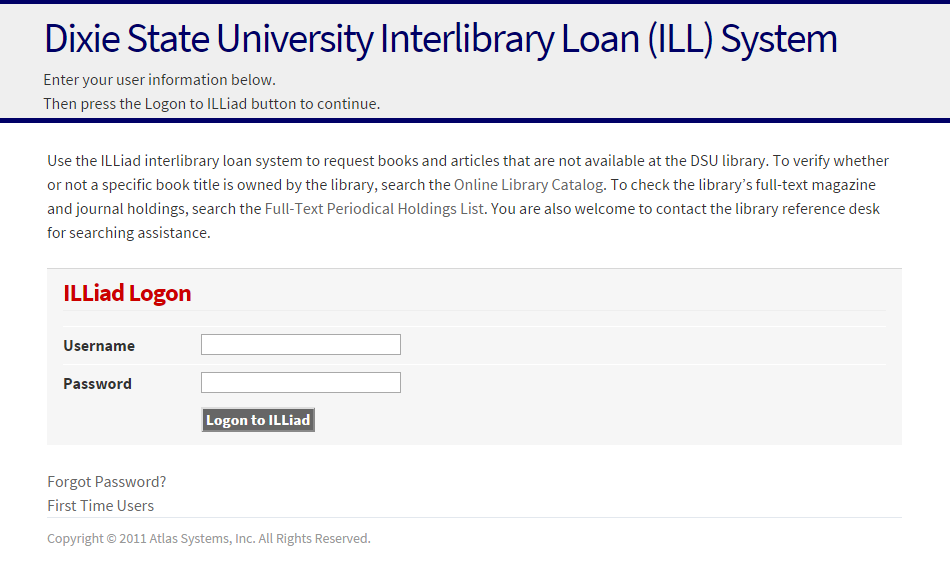

Interlibrary Loan

If the DSU Library does not have an item that you need for your research, try using Interlibrary Loan (ILLiad). It is a free service for all DSU students currently enrolled in classes. Books and articles that are not found in the DSU Library collection may be requested with the exception of textbooks. Interlibrary Loan is a system that allows libraries worldwide to share materials. The DSU Library uses an online system called ILLiad (Fig. 3C) for requesting materials from other libraries. If another library has the item, it is likely that the DSU Librarians can get it for you. Once you have set up an ILLiad account, you can request items you found in WorldCat (using WorldCat Discovery) by including all the information you found about the item (title, author, etc.). Logging into your ILLiad account will allow you to see the progress of your request. When your item is available you will receive an e-mail notification.

Links to Interlibrary Loan are found on the DSU Library Home Page (library.dixie.edu) by clicking on “Article Databases” or “Books & More”. For more information on how to use Interlibrary Loan or help searching WorldCat, visit the Reference Desk in the DSU library.

Figure 3C: ILLIAD login page.

As a student you may also borrow items from other academic libraries in the state, including Southern Utah University, Brigham Young University, and the University of Utah. When you visit an academic library in Utah, all you need to do is show your library card (DixieOne Card) to borrow from them. You are responsible for any fines incurred and must abide by any terms set by the lending library.

Two types of encyclopedias are published to provide information to readers. One type is a general encyclopedia. This type of encyclopedia contains lots of different topics and may be online or in print (Encyclopedia Britannica, World Book, Wikipedia, Funk & Wagnall’s Standard Encyclopedia of the World’s Knowledge, etc.) General encyclopedias are NOT used as a source for college-level work.

The second type of encyclopedia is a subject-specific encyclopedia. This type of encyclopedia is specialized content covering a particular subject or discipline. For example: Encyclopedia of Global Warming and Climate Change, The Gale Encyclopedia of Science, Grove Encyclopedia of American Art, and Encyclopedia of Sports Medicine.

Subject Encyclopedias are excellent tools for college-level research and provide background information about your topic. This background information can provide you with historical information, interpretations from the past, facts, statistics, and introductions to key researchers publishing in that subject. The terminology found in subject encyclopedias can be used as keywords in your research as you search databases, library catalogs, and the Internet.

For online encyclopedias, the DSU Library provides access to Sage Knowledge (encyclopedias and handbooks in social sciences, business, communication, and more), Oxford Reference Online (encyclopedias and dictionaries in humanities, languages, and more), Oxford Digital Reference Shelf, Oxford Music Online, Oxford Art Online, and the Gale Virtual Reference Library (variety of encyclopedias).

Subject Encyclopedias are a perfect place to begin your research. The online encyclopedias are listed in the Article Databases (Fig. 5A). Many online encyclopedias are also discoverable in the DSU Library Catalog (Fig. 3A).

Books can be searched using the library catalog (Fig. 3A and Fig. 3B). Books are an essential component of any research project because they often contain information not found anywhere else. They also contain a relatively large amount of information and will typically go into greater depth on a topic or subject. Books cover a range of content from the general to the specific and can refer the reader to many other useful resources including suggested reading lists and extensive bibliographies of content the author used in their research. One possible disadvantage of books is they may not be as current as other resources.

E-books contain the exact same content as their print counterpart with the added advantage of full text searching. You can type what you want to find into a search field and the entire book will be searched automatically. Since they are accessed online they are available all of the time. The DSU Library has several e-book collections that are viewable by going to the DSU Library Homepage (library.dixie.edu) and selecting “Books & More.” Then click on “E-book Collections” (Fig. 3A).

When searching the e-book collections, simply click the title of the database. If you are off campus, enter your username and password (this is your DixieID and password). Why search e-book collections directly? Doing so will allow you to search the full-text of every book in that collection.

E-books are also discoverable from the DSU Library Catalog (Fig. 3A). If accessing an e-book from the DSU Library Catalog, a direct link to the e-book is available. Click on the electronic access link. If you are off campus, enter your username and password (DixieID and password). For additional assistance accessing the e-book collections and how to navigate each interface, please visit or call the Reference Desk.

When you begin to gather resources for your research paper, the best way to start is to develop a list of keywords. This list of keywords is the essential words that make up your topic. For example, if you are writing a paper on a correlation between post-traumatic stress disorder and unemployment in women living in the United States; keywords that you would want on your list might be:

Once your list of keywords is complete, you can then develop a list of equivalent terms. Equivalent terms are defined and detailed below.

Using keywords is a way to eliminate unneeded or common words in your search that may weaken the results. When using keyword searching, capitalization does not matter and will not make a difference in the search results.

After you develop a list of keywords, you may want to develop a list of Equivalent Terms. Equivalent terms are words that serve the same purpose in your search. They may be synonyms (have the same meaning) or have similar meaning to other words used in your search.

Putting search phrases (more than one word that should be searched together) in quotation marks forces the words to be searched together, in the order you had entered them in. This technique will function in library catalogs, subscription databases, and on the Internet using search engines like Google.

“nuclear waste” storage = nuclear waste and storage

“greenhouse effect” will look for the concept of the greenhouse effect and not the word “greenhouse” and “effect” separate or isolated from each another.

Phrase searching forces the search to retrieve the phrase and not the terms independent of one another. If you were to search greenhouse effect without the quotes you may retrieve (depending on what you are system you are searching) a website about how to build a garden greenhouse or an article about the effect of smoking on adult heart health.

One method of organizing information includes using Controlled Vocabulary. Controlled vocabularies refer to terminology (words or terms) that specific databases use to describe the content of resources. Each article has specific words or terminology assigned so that you are taken directly to related articles when you search the database using its controlled vocabulary.

Using a controlled vocabulary is like knowing what to ask for in a grocery store. For example, if you like soda, you may also prefer a certain brand or flavor. If you were to go to a grocery store and ask where to find cherry flavored diet Coke, you will have used controlled vocabulary that the grocer understands and that the grocery store uses to organize all the sodas. After you make this specific request, the grocer will take you directly to the product you want. If you did not use the correct controlled vocabulary or enough controlled vocabulary words known to the grocer you may have less successful results. You might say that you are looking for a soda and the grocer might take you to a box of baking soda. This is how controlled vocabulary works in a database when you search.

There are many systems and unique varieties of controlled vocabulary and each database company has created their own. Many databases have their own lists of controlled vocabulary that you can refer to as a guide. Controlled vocabularies might also be called subjects, thesaurus, descriptors, or subject headings.

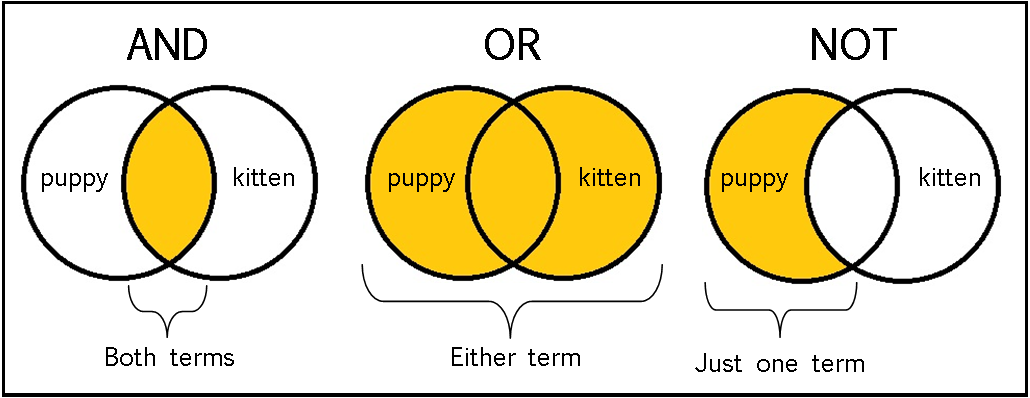

Boolean (or Logical) Operators are connectors that establish the relationships between search terms. They provide directions to the database on how to search for keywords and the order in which the search is to be conducted. The name “Boolean” is after George Boole, a nineteenth century English mathematician considered the founder of logical algebra. The most common logical operators are: AND, OR, NOT.

Capitalizing logical operators is done in the LIB 1010 course for clarity in the modules, but is not required when searching the DSU Library databases.

AND

The Boolean operator “AND” is used to narrow search results. If you are retrieving too many records or the results are too broad, add a new search term connected with “AND.”

Example: drugs AND teenagers

Results will contain both the term “drugs” and the term “teenagers” and requires both terms to be present.

Adding unlike terms connect by “AND” is a much more efficient method of limiting search results.

OR

If you are not getting enough results or want to expand the results, add an equivalent term connected with “OR.”

Using the Boolean operator “OR” is most effective when used with similar terms (equivalent terms.) “OR” broadens a search because it produces more results than any of the terms searched alone.

Example: crime OR theft

Results will include either the term “crime” or the term “theft”—or both terms. Using the Boolean operator “OR” requires at least one of the terms to appear in all results and the search will retrieve any of the terms, anywhere in the item, in any order. Use the logical operator “OR” to connect additional, similar terms to give the databases choices and you can keep adding equivalent terms connected by “OR.”

Example: pencils OR pens OR markers.

NOT

If you are retrieving too many records on an unrelated topic, try eliminating a word by using “NOT.” Only use the Boolean operator “NOT” when irrelevant items are overwhelming relevant results. Keep in mind that using “NOT” may eliminate useful results in some instances.

Example: depression NOT economic

The results in this search must contain the term “depression” and must not contain the term “economic.”

Example: trees NOT pines

Searches that include a “NOT” require the second term to be absent in any of the results. In Google “NOT” is the minus sign ( - ) and will achieve the same effect in your searches.

“NOT” narrows a search, but it can be dangerous. What if the result was about your topic and only briefly mentioned the second word?

Truncation is a technique of cutting a word off to its root and using a symbol to stand for all possible endings of that word. For example, a search for the term “pollution” may be too limited. Why not try truncation so you can get all forms of the word pollution? Truncation is shortening a word down to its root and including a symbol at the end of the root. Some databases use different truncation symbols, but the asterisk symbol ( * ) is the most common. In the DSU catalog, the truncation symbol is the ($).

Pollut* = pollute, pollution, polluted, pollutant, polluter, pollutive, etc.

Truncation is a great tool to use for singular and plural nouns as well as verb forms. It also is a way to get around the controlled vocabulary in the databases.

Databases process search terms, in order, based on how you conduct your search statement. For a more accurate result list, group your search terms for the database using parentheses ( ) to group like terms. This creates a search statement.

There are five rules of search statements:

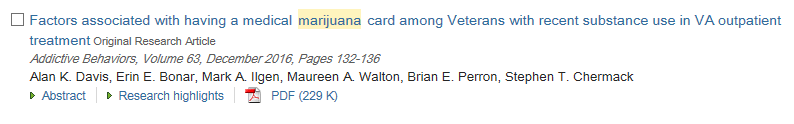

The term “periodical” refers to publications (journals, magazines, and newspapers for example) that come out periodically (daily, monthly, bi-annually, etc.). The term “article” refers to the pieces of content in a periodical.

For example, if using the Addictive Behaviors and reading something titled: “Factors associated with having a medical marijuana card among Veterans with recent substance use in VA outpatient treatment” then the periodical is the Addictive Behaviors and the article is the “Factors associated with having a medical marijuana card among Veterans with recent substance use in VA outpatient treatment.”

Some advantages of using periodicals in your research include:

Some disadvantages of using periodicals may include:

The DSU Library holds periodicals in print and in digital form. Those held digitally are found and accessed in the Article Databases (Fig. 5A). Those found in print will be found using the DSU Library Catalog (Fig. 3B).

To access articles held in any of the online databases go to the DSU Library Homepage (library.dixie.edu) and click on “Article Databases” (Fig. 5A). If you are off campus, you may be asked to enter a username and password (use your DixieID and password.)

PERIODICALS (There are 4 main categories)

| Scholarly Journal | Trade Publication | Popular Magazine | Newspaper | |

| Author: who wrote the articles? | Experts in their field and have conducted original research in the topics written about in the journal | Workers in a specific industry. | Staff writers employed by the publisher; freelance writers. | Staff writers or columnists employed by the newspaper. |

| Audience: who is this written for? | Researchers, academics, and professionals | Industry specialists or professionals; professional writers; vendors or representatives. | General public. | General public; may be local, regional or national audience. |

| Review & Editing Process | Peer-reviewed by other experts in the field or subject area; Peers check the article for validity and accuracy before publication. | Professional editors usually employed by the publisher. | Professional editors | Professional editors usually employed by the newspaper. |

| Content & Documentation | Current research and scholarship; list of references, bibliography; uses technical/scholarly language. | Specific to a particular trade, occupation, or industry; Industry trends and news; Technical language that is industry specific. |

Current topics and interests; Uses simple or non-technical language; Rarely includes references. |

Information and reporting on current events and have a local or regional focus; Content may be retrieved from newswire reports; |

| Advantages | Peer review; Authoritative and written by experts; Many are available in digital form and are searchable in full text; Based on research and contain critical analysis or original findings; Extensive lists of sources are provided to help you identify other sources (bibliographies). |

Authors are specialists in the industry Cater to a single-interest group or specific industry or profession |

Current topics Short in length |

Local or regional emphasis Current information |

| Disadvantages | Technical language and assume that fundamentals are understood by the reader; Addresses very specific questions and is narrowly focused; |

No peer review; Emphasis on commercial interests. |

No peer review Potential bias and spin Sensationalism and misinterpretation of findings and events by inexpert authors |

No peer-review Potential bias and spin Insert comparison table so that students can see the difference between the different types. |

| Examples | New England Journal of Medicine, the Journal of Science Communication, or the Journal of Atmospheric and Oceanic Technology. | Concrete Monthly, The Engineer, Nursing Standard, The Biologist, or Music Week. | Newsweek, Sports Illustrated, Rolling Stone, or the New Yorker. | Wall Street Journal; New York Times; USA Today; or Salt Lake Tribune. |

Article Databases contain thousands of articles and can be accessed through the library web site. If you are on campus, you can access the article databases instantly. If you are off-campus, you will be prompted to enter your DixieID and password before gaining access.

The article databases are accessible by clicking the link highlighted in the image below (Fig. 5A) and will give you access to all of the DSU Library databases.

Article databases are organized collections of articles and other materials you can use for your research.

Figure 5A: The DSU Library Homepage with “Article Databases” selected.

Several options are available for exploring databases on the DSU Library web page including an Alphabetical List, a General/Multi-Subject List, a Subject List, and a Full Text Periodical’s List.

Click on the Alphabetical List to see every database listed by title alphabetically as well as a brief description of each database. Simply click the title to go directly into each database.

Click on the General/Multi Subject List to see databases that cover many topics. These databases are the largest, most comprehensive full text resources and are a good place to go when beginning your research. A large amount of content you will find is available in full text (meaning an entire article) but some of the content is given to you as a citation only. This means you are provided information about the article, but not the article itself. This citation information (title, author, volume, issue, etc.) will be essential if you decide to request the item through Interlibrary Loan.

Click on the Subject List to see a list of resources associated with an academic discipline or area of research. Simply find the subject you are interested in and select it to see all of the databases associated with that subject.

If you click the Full Text Periodicals List you will have the ability to search for periodicals and retrieve information showing which database contains the periodical you have entered. You have the ability to search by title or by ISSN. An ISSN is a unique 8-digit number that is specific to an individual publication in a specific format either as a print publication or as a digital edition. If you know that number, you can search for the periodical by that number. ISSN is an acronym for International Standard Serial Number. If the result indicates there are no holdings, you may order it through ILL.

Databases each have their own unique focus and uses. When selecting a database from the DSU Library web site you may notice the name of a vendor, in parentheses, next to the name of the database. Vendor names may include EBSCO, Elsevier, Alexander Street Press, ProQuest, or Gale, to name just a few. The vendor name is the company that compiled, created, and continues to maintain the database. Each company has a different database interface for searching and each will have a unique look to separate it from other vendors. This is similar to Yahoo! internet search engine vs. the Google search engine; each is made by a different company.

Most database search features are available in any database regardless of the vendor. This section introduces those features and how to use them. For more information about each vendor database and demonstrations on each feature, search YouTube and/or the vendor’s website for tutorials. For further assistance and help with your searches, talk with a librarian at the Reference Desk in the DSU Library.

Results List, Ranking, and Sorting

Once you put in your search terms, the database gives you a list of results. The items are listed by relevance, which means that the articles that match closest to the terms you used in the search box will be closest to the top of the list. This can also be changed to be in order by date (from oldest to newest or newest to oldest), and in some databases by the name of periodical or even the author.

Abstracts

Abstracts are short summaries of an article or book so that you can review what the article topic is about before you decide if you want to use it for your research. They are often found in the item record or at the beginning of an article.

Link Resolver (Check for Full Text Link)

If there is no full text option (PDF or HTML) available, in most databases you will see a link that says “Check for Full Text”. By clicking this option other databases are searched to find the article. If it is found in full text, it will display the article for you. If full text is not available through DSU Library databases, you can order the material through Interlibrary Loan.

Advanced Search, Refinements, and Limiters

Most databases will have an advanced search feature and can usually be found as a link near the general search box. By using this feature, you may be able to refine or limit your search to be more specific. This way your results list will have articles listed that are useful and specific to the type of information you need.

Some other ways you can limit or refine your results is by using features like selecting a date range, geographic location, main subject, and type of publication (scholarly journal, magazine, trade journal or newspaper).

The Internet is a term that refers to the large network interconnection of many computers in the world. It allows these computers to “talk” to one another and facilitates information exchange. The Web (or World Wide Web) is a portion of the Internet that typically uses browsers and specific protocols (like HTTP) to access and distribute information. These terms are frequently used interchangeably, but for the purpose of this class we will use the term “The Internet” to reference either.

The Internet can be a powerful and extremely useful tool for your research. Content from the Internet (including blogs, web sites, videos, articles, news, etc.) can serve as valuable sources of information to include in your research paper or project. The quality of the source may vary so careful evaluation is critical.

Truncation, controlled vocabulary, and browse searching are excellent tools for searching in Article Databases, but they are not effective in all internet search engines. While the use of logical operators is limited, the most important search technique in internet search engines is “phrase searching.”

A web browser is a piece of software that allows you to search the Internet. Web browsers send requests to web servers and allow users to view and access information. A web server is a piece of equipment (in other words: computer hardware) that stores the content found on the Internet. Some of the most popular web browsers are Microsoft Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, and Apple Safari.

Search engines are needed to search the Internet. These search engines build huge databases of web content (pages) and enable users to search those databases. Some examples of search engines include Google, Yahoo! Search, Bing, and Wolfram Alpha (numbers). Different search engines produce very different results even when using the same search terms. Some will automatically put “AND” in between each of the keywords that you might enter. For example, a search using the words nuclear waste storage could be transformed into the search: nuclear and waste and storage. This has the potential of greatly impacting the results.

Eliminate unneeded and/or common words such as articles (a, an, the), interrogatives (who, what, where, when, how), and prepositions (in, for, at, etc.) Punctuation is ignored except for apostrophes (hadn’t, didn’t), dollar signs to indicate prices (nikon 400 vs. nikon $400), hyphen (for example: low-budget; hyphens are read as minus sign if preceded by a space), underscore (quick_sort)

Question: what is the truth about global warming?

Search: truth global warming

Here are some other tips for searching the internet. Capitalization doesn’t matter. For example: Utah = uTaH = Utah. Try to eliminate unwanted terms by using a “minus” sign. For example: “nuclear waste” storage -medical. This will remove the result if the term medical would have otherwise appeared.

Google automatically stems words. So for example a search for “run” will also return

If you want to stop Google from stemming, use the plus ( + ) sign in front of the word (+run).

To search synonyms, use the tilde (~) key. For example: ~car will retrieve car, cars, automobiles, vehicles, etc.

Google also provides advanced searching. If you visit http://google.com/advanced_search, you will be able to use advanced options like searching within a site or domain (for example you could search within dixie.edu or for material found on only websites with the .gov domain extension), limit results by date published/updated, limit results by language or region, limit your search by file type, and more.

Google offers search options that limit your search to images or videos. Google also offers a tool called Google Scholar (scholar.google.com). From there, you will be able to search for materials that often come from scholarly sources such as .edu websites, scholarly journals/publications, and the like. If you are on campus, Google Scholar links directly to some articles in the DSU Library databases.

Some parts of the Internet cannot be accessed by search engines. This portion of the Internet is called the invisible web. The invisible web contains contents like bank records, medical records, Department of Defense secrets, etc. It also includes many library databases. This database content you have access to as a student, through the DSU Library, but not directly accessible through search engines. To search these databases, you must go through the DSU Library web site at library.dixie.edu and if you are off campus you must log in. The DSU Library subscribes to the content in these databases. They are part of the invisible web as they are a tool that you must log into. Most of the information that is part of the invisible web requires you to log in and have a password.

Content that you discover on the Internet is often found on a web page. A web site is a collection of web pages. A web page is an online document that you can view using a web browser. These documents contain text, a variety of multimedia components (video, animations, images, etc.), downloadable content, and links to other web sites. Web pages have an address so that you can locate it by typing in the address. This address is also known as a URL (Uniform Resource Locator). The Uniform Resource Locator is the address of a web page and appears like this example: http://www.dixie.edu

Each address is made up of several parts. Using the example above, each part is explained here briefly:

| http:// | This portion represents what is known as the HyperText Transfer Protocol. This is the “language” of the Internet when it comes to web addresses. |

| www | This portion is not included on all web addresses and some work without it. It stands for World Wide Web. |

| .dixie | This portion is the domain of the web page. |

| .edu | The domain extension of the web page. |

Other domain extensions used on the Internet include:

| .edu | Educational institution, college, university, or research organization with a bona fide U.S. presence. |

| .com | A very common domain extension typically a commercial or business enterprise. |

| .gov | U.S. government entity |

| .mil | U.S. military entity |

| .net | A general purpose domain extension (and the second most common on the Web) |

| .org | A not-for-profit entity (including churches, K-12 schools, charities, political groups, etc.) |

Valuable research material can also be found from other online sources such as websites, blogs, podcasts, YouTube, social media, etc.

Evaluating websites and other resources is important to ensure that the sources you are using are credible and accurate. At DSU we use the CRAAP Test to check the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy and purpose of resources being used for papers and assignments. The CRAAP Test includes a list of questions that can be used to evaluate information that you fine. This is particularly important in the evaluation and use of websites. View this video to find out how to use this test!

Currency: the timeliness of the information

Relevance: the importance of the information for your needs

Authority: the source of the information

Accuracy: the reliability, truthfulness, and correctness of the content, and

Purpose: the reason the information exists

Evaluating information: Applying the CRAAP Test. (2010). Retrieved from http://www.csuchico.edu/lins/handouts/eval_websites.pdf There is also a CRAAP worksheet for you to use in Module 6.

You many wonder why instructors require you to use different types of formats when gathering your sources for a research paper. For example, they may ask for three peer-reviewed journals, one book, and two authoritative web sites. The answer is simple. Different formats = different content.

What you find in a book, you won’t necessarily find in a journal; the content of a newspaper is very different from the content of an encyclopedia, and websites contain information that is quite different from that found in a scholarly journal.

There are other important factors to consider when evaluating sources, regardless of its type or format. One factor relates to the usefulness of the information. To be useful, an information source must be relevant to your topic and purpose. It must have the appropriate degree of credibility required for your audience. Scholarly works, including entry level undergraduate college assignments, require reputable, academic sources.

The focus of the item should be that it is primarily “about” your topic, as opposed to just mentioning your topic. It also needs to be in an appropriate format, by a credible author, with suitable sourcing. Read the abstract or summary to determine how relevant it is for the project you are working on.

Start your research project early and include a variety of resources in your work. You may need to use Interlibrary Loan to get the sources you need and that can take time (an average of two weeks for books and an average of 2-5 days for periodicals). Give yourself enough time to find and obtain all of the sources you need. Ask for help from the librarians at that DSU Library Reference Desk if you need assistance.

The ethical use of information includes four elements covered in LIB 1010:

The public domain refers to content and materials that are available to the open public and are not subject to copyright (also known as copyright free). Anything published before 1923 is in the public domain and can be used by anyone for any purpose. All publications of the U.S. government are in the public domain. Other items are specifically created to be copyright free. These include works that are marked “license free” and “public domain”. Just because the original of a work was published long ago (like the music of Mozart) does not mean that their published versions are copyright free. Even an item in the public domain needs to be correctly cited to avoid plagiarism.

Intellectual property is any creation of the intellect that has commercial value.

There are different types of law to protect different types of creation.

The U.S. Copyright Act enacted in 1790 by the first Congress of the United States was a key event in the history of copyright law. Today, Title 17 of the U. S. Code is the Copyright Act and is a federal law. It was revised in 1976 to include the “Fair Use” Doctrine (detailed below.)

Copyright law gives the author (or other copyright holder) exclusive rights to the use of that work for a defined period of time. Fair Use allows copyrighted material to be used without permission in very specific and limited circumstances.

Other revisions included the 1998: Copyright Term Extension Act (CTEA), also called the Sonny Bono Copyright Term Extension Act (or the Mickey Mouse Protection Act). This revision stopped the progress of copyright expiration with works published before 1923. Anything published in 1923 or later is still protected. Anything under copyright in 1998 will remain copyright protected until at least 2018. No designation or registration is needed for a work to be protected under copyright.

The Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA) applied specifically to electronic/digital materials and limited fair use for digital (electronic) materials. It provided for stricter rules and higher penalties for copyright violations involving electronic and digital content.

Why is this important?

Violating copyright is breaking the law and monetary judgments in the form of restitution to copyright holders or fines might accrue for copyright violations. Businesses are liable for damages caused by copyright infringement. This means you may be putting your employer at risk if you are not careful. Breaking copyright law inhibits the purpose of the law to help foster creativity and provide an environment when knowledge can grow by protecting those who create.

Copyright applies to any original, creative work with some aspect fixed in a tangible (including digital) format. It applies to:

The works of Mozart (and Jane Austen and William Shakespeare and thousands of others) are copyright free because they were published before 1923, but the context is not. A published work of Mozart is protected. You can’t copy and distribute the music without permission. The publisher’s font, arrangement, organization, layout, etc. is protected. However, you can publish your own version of Mozart’s original work and sell it.

Just like adherence to most laws, it is your responsibility to follow copyright laws as part of using information ethically. Be especially careful if you violate copyright while in a position with any organization that can be seen to hold assets, even not-for-profit organizations like schools, churches, or charitable organizations. The presence of assets may make it worth the time and effort for the copyright holder to seek a judgment against you or the organization you are representing. Even if the eventual decision is in your favor, the legal and other costs associated with defending fair use (detailed below) can be substantial.

Copyright laws are consistently being strengthened, and no individual or entity is exempt, no matter how geographically (location) remote or motivationally virtuous their intent (innocent, charitable, or a good cause).

Still need help knowing what is copyright? Go to the library’s Research Guide on Copyright and Fair Use and Plagiarism: Library Homepage > Research Guide > Copyright http://libguides.dixie.edu/Copyright

The Fair Use Doctrine tied to copyright law provides legal use of copyrighted material without permission under specific situations. Fair use usually excludes commercial enterprises (other than news reporting, criticism, and commentary.)

Fair Use allows copyrighted material to be used in academic situations, under strict rules for teaching, research, and scholarship.

When a judge has a fair use case before him/her the outcome of the case will depend on these four items:

Fair Use allows you, as a student, to make copies for your personal research. One thing that fair use does cover is making a single copy (in print or digital format) of almost any material for scholarly or research purposes. Most of what an individual student does in a college course is covered by fair use, especially if he/she rigorously works to prevent plagiarism. The restrictions on multiple copies, even for teachers, are much stricter. Before you push “print” on a photocopier or computer, consider carefully if you should get permission, even if the purpose is listed above.

Just because you may not reap financial benefits from the use of an item does not make it fair use. Even if you don’t charge a fee, you may still be cheating the copyright holder. Just because you are doing something for a “good cause” (not-for-profit organization) does not make it fair use. If you are depriving the copyright holder from earning justifiable income from his/her work, you may be in copyright violation.

The rules become even stricter once the student is no longer in an academic, scholarly, research environment. If you are depriving someone of earning income by circumventing the purchase of the item (photocopying, printing, digitizing, or recording material without permission, for example) you are probably in violation of the law. Fair use does not mean that any not-for-profit organization can use copyrighted material without permission. It does not mean that because you’re not charging a fee you can use copyrighted material without permission. Remember, most content on the Internet is “owned” by someone. The World Wide Web is not a free grab bag of intellectual property for the taking.

So, how do you know if something is protected under copyright?

Copyright only applies to tangible works—not ideas, but physical manifestations of ideas. Additionally, registration or use of the copyright symbol is no longer required. Keep in mind that facts cannot be copyrighted, but their interpretations and contexts can be. Also remember that copyright applies to more than just written work.

Even without a copyright symbol or other notice, you must assume that a creative work is protected under copyright. Creative work does not apply to artistic sensibility in this case. In copyright terms, “creative” refers to the originality of the work as a production of the human mind. To be copyrighted, a work has to be produced in some form. This includes web sites. Just because something is available on the World Wide Web doesn’t make it copyright free! In fact, most good information online is copyrighted.

You must get permission to use copyrighted material in all cases other than Fair Use. Most people who hold copyright on an item are willing to give others permission to use it. Whether or not there is a fee will often depend on the copyright holder’s beliefs, the use you propose, the extent of that use, the market for the item, etc. Considering copyright permission can be a useful test for someone considering using the copyrighted work of another. Consider the request; would you agree to it if you had created the original material and depended on your livelihood for its sale? If the honest answer is no, then you shouldn’t use it without permission.

Plagiarism is using the words, thoughts, or ideas of someone else without giving appropriate credit and it can be accidental or intentional. Plagiarism is a serious academic infraction. For college level research you are expected to use outside sources, especially the work of experts. You must also know how to integrate those sources properly so you avoid plagiarism.

Copyright and plagiarism are both very serious, but they’re also very different. Plagiarism is an academic infraction created by incorrect or missing citations of the words, thoughts, and ideas of others. Copyright applies in all situations to tangible creations. It is a Federal crime to violate copyright. Fair Use exempts student researchers from the copyright law under certain conditions, but researchers must abide by the rules of scholarship, including avoiding plagiarism.

According to the DSU Student Rights and Responsibilities Code (Section 5, Policy 33), plagiarism and copyright violation are prohibited activities:

XI, A, ii. Plagiarism: “Includes but is not limited to the use of another’s words or ideas as if they were one’s own, including, but not limited to, representing, either with the intent to deceive or by the omission of the true source, part of or an entire work produced by someone other than the student, obtained by purchase or otherwise, as the student’s original work or representing the identifiable but altered ideas, data, or writing of another person as if those ideas, data, or writing were the student’s original work.”

XI, A, viii. Copyright Violation: “Includes but is not limited to copyright and other violations of the College’s policies. Such matters are adjudicated under the Student Behavioral Conduct section of this code.”

Consequences for violating the DSU Student Code include: Warning, reprimand, grade adjustment, academic probation, suspension, expulsion, fee assessments, restitution, denial of degrees, etc.

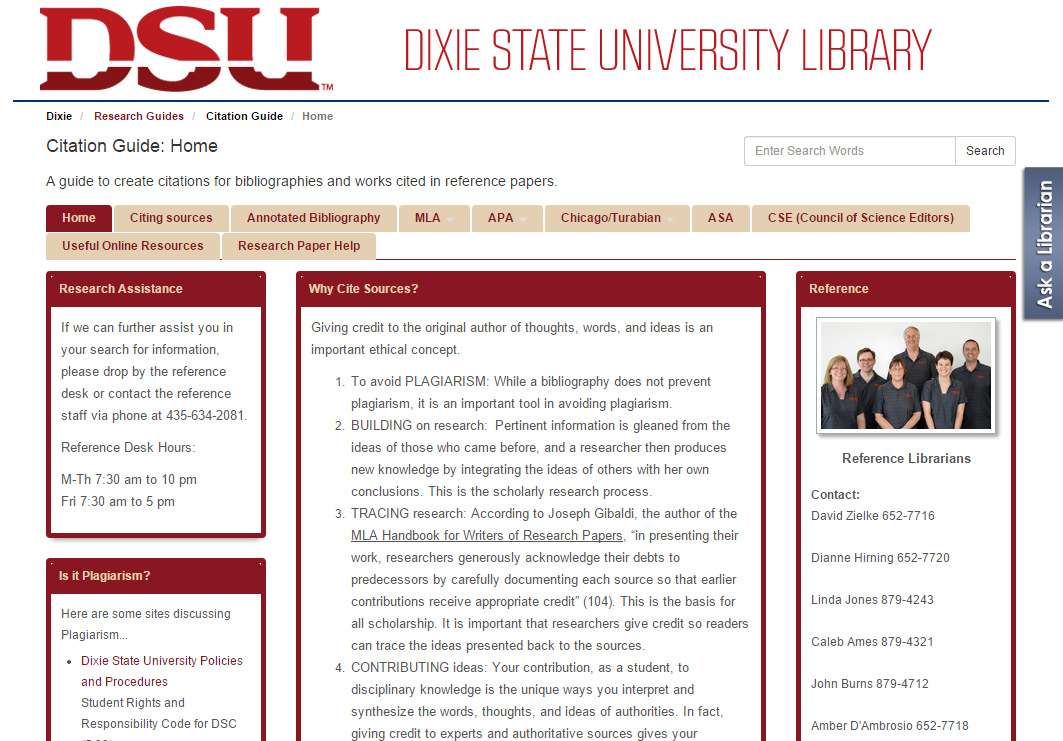

Research Guides are available through the library web site and can assist you with subject specific research and bibliographic citations. Clicking on the Citation Guide will display (Fig. 8A) online guides and information on creating citations in MLA, APA, Chicago/Turabian, CSE, and ASA citation styles. The Citation Guide also contains many other useful resources and information for you including information on how to create an annotated bibliography.

The Research Guides also features subject specific guides that can help you find key materials and resources for your papers and projects. Click on “Browse Other Guides” to see guides on any subject that you may be studying at DSU. For more information on a particular subject, each guide provides librarian contact information.

Figure 8A: “Citation Guide” displayed on the DSU Library website.

Creating citations and bibliographies are ethically important. If done properly, they help you avoid plagiarism and gain the essential skill of integrating source material into your own work.

There are two parts to giving credit to the work of others that you would like to reference in your work:

To integrate or use source material in your work you have three options. The first option is to paraphrase the material from the resource you have chosen. Paraphrasing is the act of rewriting or rewording the source material into your own words. Paraphrasing will be about the same length as the original source material. By placing paraphrased source material into your work you establish a connection to how the source material relates to, supports, or disagrees with your topic and ideas.

The second option is to summarize the material from the resource you have chosen. Summarizing is the act of condensing source material into main points and giving a synopsis of the content. The synopsis and main points are integrated with the purpose of establishing how the source material relates to, supports, or disagrees with your topic and ideas.

The third option is to quote the material directly from the resource you have chosen. Direct quotes are given in your work exactly as they are written (or spoken) in the source. They are word for word identical to the source they originated from. Including direct quotes establishes a connection of how the source material relates to, supports, or disagrees with your topic and ideas.

Citing the source material you use is an act of documenting that you are giving credit to the creator or author of the source content (their words, thoughts, or ideas.) Many of the papers that you write in college will consist largely of quoted, paraphrased, or summarized material from others who are experts in their field. Often, the source material that will help your paper the most will be original research written by the people who conducted the research (experiments, surveys, primary studies, etc.)

There are two kinds of citations that you must use in any academic paper. One is an in-text citation and the other is a bibliographic citation.

When quoting, paraphrasing, summarizing, or referring to the words, thought, or ideas of others, use a short reference within the text or in a footnote (depending on the citation style). This refers your reader to a specific item (and often a specific place within that item) listed in the bibliography. In-text citations within your writing also include a signal phrase (also known as a signal tag) such as “According to Dr. David Smith…”

A bibliography is a list of source material and is typically found as the last page of your paper. An annotated bibliography is a list of sources that you found for your topic and a short annotation about that source. Depending on your instructor’s use of this bibliography, the annotation could be a summary about the source or an analysis on how you will use the source in your research or an analysis about the source itself.

A bibliographic citation is each entry or item on that list at the end of your paper, speech, or presentation that lists all the sources you cited (quoted, paraphrased, or summarized) within the paper. The bibliographic citation is the basic, pertinent information needed to find the full text of a publication and these citations make up your bibliography. The bibliographic citation gives an accurate, precise, uniform description of the source material. A bibliographic citation will document what format the source material is in. Format is the form that the content comes in and is used to communicate that content. Common material formats include print (periodical article or book), online book (e-book), online periodical article (from a database or a web site), journal, magazine, newspaper, web site, video recording, personal interview, or personal communication.

View the Module 8 PowerPoint in the modules for more information.