The Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

Young “Tony” Ivins: Dixie Frontiersman

by Dr. Ronald Walker

St. George Tabernacle

15 March, 2000

Val Browning Library

Dixie College

St. George, Utah

with support from the Obert C. Tanner Foundation

About Juanita Brooks

Juanita Brooks was a professor at Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author.

She is recognized, by scholarly consent, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been life-long friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her name through this lecture series. Dixie State College and the Brooks family express their thanks to Dr. and Mrs. Tanner.

Young “Tony” Ivins: Dixie Frontiersman

He was one of the few remaining pioneers of the Old West, and one of the greatest.

Herbert S. Auerbach

Salt Lake Tribune, September 25, 1934, 7.

My experiences on the frontier…may be of some historical value, as well as romantic interest.

Anthony W. Ivins, “Autobiography.”1

Nine-year-old Tony Ivins was playing at a friend’s house in the Fourteenth Ward when John M. Moody, the father, returned from attending a session of the LDS general conference. He had startling news. The Moody family had been called to settle in southern Utah. For Tony, this was exciting information. Not taking the time to go around the block, he “cut cross lots,” climbed a fence, and ran through the family garden. Entering his house, he saw his mother and sister talking quietly. “Brother Moody is called to go to Dixie to raise cotton,” Tony blurted. It was then that the boy noticed his mother’s tears. “So are we,” she replied.2

Ivins later wrote: “Present plans, future hopes and aspirations, ties of kindred, the association of life-long friends and neighbors were all to be shattered and swept aside as we started on this new adventure, the outcome of which no one could even surmise.”3

What makes a man or a woman? What are the forces that shape a personality, determine a life, or in the biblical language of Ivinses’ generation brings at death “a shock of corn…in his season?”4 For Anthony W. Ivins (1852-1934), a prominent Dixie pioneer, an Apostle in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and later a member of his church’s First Presidency, there were several answers to these questions, which included family, friends, and place. Each mingled in Tony Ivins’ early life.

Ivins’s family came from New Jersey. His earliest New Jersey progenitor, Isaac Ivins, settled at Georgetown in 1690, where he prospered by trading with Indian trappers and white hunters. Later members of the family used the bonds of marriage and the flow of commerce also to achieve financial success. The Ivins’ counted among their marriage relations such New Jersey gentry as the Allen, French, Lippincott, Ridgway, Shreve, Stacy, and Woodward families. In business, James and Charles Ivins thrived as merchants in the town of Upper Freehold. Caleb Ivins, Tony’s great-grandfather, owned Hornerstown’s distillery, country store, and grist and saw mills—and had farm lands and orchards as well. Twenty miles to the southeast at Toms River, Anthony Ivins, his maternal grandfather and also a merchant, resided at “The Homestead.” This large house had handsome paneling, stairways, and mantels and was recognized as one of the best examples of colonial architecture in the area. In turn, Tony’s paternal grandfather owned large tracts of land that yielded wood and charcoal—commodities that were shipped to New York and elsewhere in Ivins-owned ships. Related to each other as first, second, or third cousins, the New Jersey Ivins were “considered wealthy, and stood high in the community.”5

Tony’s parents, Israel Ivins (1815-1897) and Anna Lowrie Ivins (1816-1896), continued the tradition of keeping marriage within the family. They were distant cousins, both surnamed Ivins at birth. As a young man, Israel worked in the family businesses and learned the skills of a surveyor on the side. There was also a hint of wanderlust; he was remembered as a “sea fairing man,” who was “as much at home on the water as on the land.” He liked sports—an expert with a hunting gun and fishing rod. In addition, he had a serious side. His avid reading gave him a reputation of being a great student. In his later years, he turned to medicine and the healing arts.6

During the late 1830s and early 1840s, wave after wave of religious excitement rolled across the central New Jersey countryside, with Methodists, Baptists, and Presbyterians vying in their ministries. But none of these denominations attracted the various members of the Ivins family as much as a new religion of “Mormonism,” officially The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Benjamin Winchester and Joshua Grant were the first Mormon elders to arrive. When entering Caleb Ivins’s house at Hornerstown in 1837, they announced they bore a special message of providence. Later they and began teaching in a frame school house about one mile west of the hamlet.7 Caleb Ivins was likely Anna’s father.8

“As to our principles, and rule of faith, the people knew nothing, except by reports,” Elder Winchester reported. The Mormon preaching stressed Bible Christianity, and it had much appeal. “It was so different from what they had expected,” Winchester recalled, that “it caused a spirit of inquiry, so much so, that I had calls in every direction.” The missionary struggled to fill as many as eleven weekly preaching appointments, with both “the rich and the poor” inviting him into their homes for personal instruction. The more he taught, the greater the excitement. In religiously charged rural New Jersey, Mormonism became “the grand topic of conversation,” the cause célèbre.9

Taking advantage of the excitement, the Latter-day Saints soon had a cadre of some of their most able missionaries in the area—Lorenzo Barnes, Jedediah Grant, Orson and Parley Pratt, Harrison Sagers, Erastus Snow, and Wilford Woodruff. Even Joseph Smith, the Mormon prophet, preached at the “Ridge” above Hornerstown. The results were considerable. By the late 1830s, the Church had several hundred converts and small congregations at Cream Ridge, Greenville, Hornerstown, New Egypt, Recklestown, and Shrewbury. Several of these even had their own unpretentious chapels. Later in the 1840s, LDS converts apparently founded a small fishing village on the New Jersey coast which they named Nauvoo. The name, of course, came from the LDS headquarters city, located in southwest Illinois.10

The Ivins family found themselves drawn to the new doctrines. This family had a tradition of running against the popular religious grain. Many branches of the family tree were Quaker. At least one ancestor, Mahlon Stacy, was proselytized by George Fox himself. Other Quaker forefathers came to America to avoid the persecuting local episcopacy—and constabulary. However, by the time of Israel and Anna, the commitment to the Society of Friends had begun to wane. Anna’s parents were Baptists, while cousin James Ivins and uncle Richard Ridgway were Baptist trustees.11

These new Baptist connections could not withstand the Mormon onset. During the first week of March 1838, Israel Ivins was baptized a Mormon. He was Elder Winchester’s first Monmouth County convert. Israel’s cousins Charles and James Ivins soon followed. Elder Parley P. Pratt described the latter as a “very wealthy man” and teamed up with him to reissue the Book of Mormon in the East.12 Other Gospel sheaves included Anna Ivins and most of her family, including, significantly, Anna’s sister Rachel Ridgway Ivins. Anna and Rachel were soul mates and confidants, and would remain so to the end. Cheerful and uncomplaining in the face of adversity, deeply religious, and full of self-discipline, both women also had the Ivinses’ quiet but firm belief in the family’s sense of proper social position.

We do not have the details of Israel’s and Anna’s courtship. Given their Quaker heritage, perhaps their relationship was based on an understanding of how much they shared, with reason and Christian calculation, not passion, being the most important factors. Whatever their feelings for each other, Israel and Anna were married on March 19, 1844, about six years after they had embraced Mormonism. Elder Jedediah M. Grant, who went east from Nauvoo on a Church mission, performed the service.13 The two were in their late twenties.

Some Ivins family members migrated to Nauvoo where they rose to prominence. James and Charles Ivins built what later became known as the Times and Seasons building. After dissenting on the question of plural marriage and other policies, however, they joined the Nauvoo Expositor group that eventually contributed to Joseph Smith’s death.14 In contrast, Israel and Anna remained in central New Jersey as loyal Mormons. Israel presided over the Toms River branch and at times entertained visiting church leaders such as Elder Erastus Snow. Snow borrowed a light carriage to transport his wife and child to Toms River, where they sailed an inlet with “Brother Israel.”15

Elsewhere the Mormons bore the insults and persecution of neighbors. In central New Jersey, the Saints were recognized as “respectable people … noted for sincerity, industry and frugality” and who, if necessary, could influence the enforcement of the law. When an anti-Mormon preacher disrupted one of their meetings, a local peace officer placed him under arrest.16

By the early 1850s, Israel and Anna had a comfortable life, which included several years of living in cosmopolitan New York City. Domestically, they were blessed with three children: Caroline Augusta (“Caddie”) born in 1845; Georgina (1846), who failed to survive the winter of 1846–47; and Anthony Woodward, bom on September 16, 1852 and named for Israel’s father. Yet, for these ascetic believers in the word, New Jersey Mormonism in the 1850s was a pale copy of the fervor that had once burned through the area. Besides, Mormon missionaries told Israel and Anna that they must gather to the newly built Zion in Utah. Seeking to comply with the religious demands of their faith and secure the grace coming from full fellowship, Israel and Anna decided to immigrate.

Leaving Toms River on April 5, 1853, the party — comprising “a large number of persons from Toms River and other places in the state”17 — also included the last and most staunch of the Ivinses. The fifteen years of Gospel winnowing had taken its toil, and only a small number of the original group of Mormon converts were willing to go West. These included Israel and Anna; Anna’s sister, Rachel; Israel’s brother, Anthony; Israel’s mother, Sarah; and Israel’s nephew, Theodore McKean. The party made its way to Philadelphia, boarded a train to Pittsburgh, and then floated on steamers via St. Louis to Kansas City. After visiting sites of interest in Jackson County — the old LDS headquarters in Missouri — they purchased mule and wagon outfits and began the trek west.18

The Ivinses’ train was remembered as “one of the best equipments that ever came to Utah in the early fifties.”19 Anna and Israel traveled with a milch cow and two heavily provisioned wagons. One of these was furnished as a portable bedroom, complete with chairs, a folding bed, and stairs descending from its tail gate. When the group paused during the day or stopped in the evening, Anna and Israel mounted the stairs and entered the wagon to rest. Despite these unusual and perhaps unnecessary provisions for comfort, the company made good time. On August 11, 1853, after about a 130-day journey, the New Jersey pioneers arrived in Salt Lake City. The party traveled up Main Street where they found short-term housing with their old preacher-friend, Jedediah Grant, now mayor of the city.20 During their next few years in Zion, old New Jersey friends like Brother Jedediah helped find a place for them in Utah’s frontier and uncertain society.

Israel found it difficult to prosper in Utah. He was by experience a merchant. But Brigham Young’s Zion was bone and sinew — it placed more value on the agrarian labor of pioneering than on the urban exchange table or business counter. To Young, merchants brought profit-margins, social distinctions, and the threat of a power potentially hostile to his theocracy. He therefore lashed out at merchants — “Taking that class of men as a whole, I think they are of extremely small calibre.”21 As a result, proper churchmen like Israel tried other kinds of work, often beyond their taste, training, and ability to succeed. In Israel’s case, he became a Salt Lake City policeman and on the side farmed a small plot on the outskirts of the city.22

However, his failure to make money was not just a matter of being a tradesman. Pioneering made people poor, particularly Utah pioneering, which was based on small, village land-holding. For the first thirty years of Utah’s settlement, its citizens badly trailed their fellow American citizens in the wealth owned by each household, even for those living in the Intermountain West.23 In 1850, the worth of Utahns was only a fifth of the national average and by 1870 the ratio had closed only to a third.

For some Utahns, there was a silver lining. If a family arrived early in Utah and remained in one place for several decades (“persisting,” to use the demographer’s word), their situation usually improved. The maturing Utah economy increased the value of their holdings as well as their social standing.24 But the family of Tony Ivins did not get even this benefit. By accepting the Church’s call to settle Dixie and in order to provision themselves, Israel and Anna were required to sell their Salt Lake City property.

Starting once more meant not only losing their stake in Salt Lake City, but it required the Ivinses to submit to an exacting future. Life in Dixie meant the Ivinses would have to feed and clothe themselves in a setting that lacked grocery stores, currency, merchants, investment capital, and wages for labor performed. Such a situation, historian Charles S. Peterson has observed, required “subsidies” of human effort and “a willingness to accept austere economic standards.”25 In fact, settling a new land on the Mormon frontier might require a full generation to get beyond the survival stage of living.

An inventory of the Ivinses’ outfit, which may have included much of the family’s assets, showed how poorly the family fortunes had fared since they had arrived in Utah eight years before. In contrast to their splendid Great Plains equipage of 1853, the best the family now could do was to secure an old and worn “heavy” wagon (for hauling goods), a “light” wagon with “shafts” (for transportation), a bay horse, two yoke of oxen, and a single harness — and apparently some debts that had been incurred to make the trip possible. In later years, Tony recorded the family’s sacrifice in his autobiography. After Israel and Anna sold their home on South Temple Street between Third West and Fourth West Streets, the property had become “worth a fortune.” It sat on the location where a railroad company had built is freight department.26

Although the family of Tony Ivins had fallen on difficult times — and things grew worse in coming years — the boy had some advantages. Through the influence of his parents and especially his mother, he inherited the Ivinses’ religious and social values, including that Ivins quiet drive to succeed. And he had talent. To such family and personal gifts, Tony also had the advantage of being raised as part of the St. George village community — Dixie’s version of the Mormons’ general pattern of settlement.

Outwardly, the Mormon village put a peculiar stamp on the land. It had rectangular streets often laid off at the cardinal points of the compass. It fostered grouped living. At the center of the village was the school house and the church meeting house (in early years often the same building), which later included an assembly hall or tabernacle. There the people worshiped as a community, especially in good weather. Also at the center of the village were the homes of the villagers. These dwellings sat on large lots that might exceed an acre. This pattern allowed for roominess, a setback from the street and beautifying flower gardens as well as practical and life-sustaining vegetable gardens. In Dixie the acreage near the house also permitted vineyards and fruit trees. Outside the village lay small agricultural fields of thirty to fifty acres and places where the boys might drive a few head of livestock to and fro each morning and evening. Giving further pattern to the land, the Mormon village often had unkempt outbuildings, irrigation ditches for home and garden use, and poplar, locust or cottonwood trees lined the streets, giving shade and a sense of order.27

The Mormon village was not designed to promote wealth, nor did it. One study found that a typical villager had no more than five cows or hogs, owned no machinery, and earned no wages. Crops were so limited that some settlers were unable to get through a winter without help from the local church storehouse. In economic terms, village life was based on labor-intensive, subsistence farming, which provided little margin for gain or abundance.28

It was a case of religious and social ideals being more important than money, as early Utahns set aside the quest of wealth for the cultural values of small, compact, and largely agrarian settlements. On this level, the Mormon village worked well. According to one authority, it was “perhaps the most elaborate mechanism for socialization to be found in any small community of the country,” offering opportunities for cradle-to-grave schooling, recreation, leadership training, and other social experience. It made pioneer life easier by conveying the Mormon ideals of unity, cooperation, and equality.29

What did this mean to Tony Ivins? While denied the ease of inherited wealth, he had the advantage of being a child of the Mormon frontier, which was peculiar to the general experience of most American western settlers. Elsewhere in the West, Tony might have come of age living in a mining camp or, still more likely, working on a large but isolated farm, a circumstance of U.S. land policy. But instead of helping to homestead a quarter section of 160 acres, Tony Ivins was the son of a Mormon village — that institution which left its most lasting imprint, not on the landscape, but in individual lives. Thus, young Tony Ivins mixed heredity, first-generation Mormon values, and the bequest of the red clay soil of pioneer Dixie.

The journey from Salt Lake City to southern Utah set a pattern. Leaving Utah’s capital city, the pioneers of St. George found the trail mired and several horses were lost. Later the wagons faced wind, rain, and snow since they were traveling in November. The Dixie pioneers did not travel as a group; wagons were spread along the southern road, united only by their destination. At nightfall, smaller parties seemed to coalesce, which permitted socials, especially the reels and square dancing that the Mormons were so fond of. One woman remembered: “There were meals to prepare, tents to pitch, beds to make down and take up, washing to do, bread to bake in a bake skillet. All this made our progress slow.” For most of the Dixie settlers, the 300-mile-trip took a month.30

At first the Ivinses traveled alone with their drivers, Alex Mead and John Lloyd (known as “Sailor Jack”). Israel needed help with the two wagons and apparently recruited these two Dixie-bound settlers to lend a hand. The first night out, the family stopped at Porter Rockwell’s house at the “Point-of-the-Mountain,” and the legendary Mormon scout sold them supplies that were “of great benefit to us after we reached our destination.”31 As the family traveled farther, they visited two families that they had known in New Jersey who had already settled in southern Utah and who extended hospitality. The climax of their trip came as the wagons drove up the grade from present-day Washington and passed over a “rough volcanic ridge” that at first concealed their view.

Then they saw.

“It was a barren uninviting landscape,” Tony said.32

These same words were used by another 1861 pioneer. When her party entered the St. George site, she saw Anna and Caddie Ivins standing and looking over the land. Perhaps there was something in their manner that appeared forlorn. “I have often wondered since what these two women must have been thinking as they looked over the barren, uninviting country that was to be their home,” she later wrote.33

In one respect, St. George was cut from a different pattern than other Mormon settlements. After sampling pioneer diaries, one study found that “individual choice” and not church direction played an “overwhelming role” in determining where and how the people settled; newcomers learned where friends or relatives had earlier settled and then traveled to that location on their own.34 In contrast, St. George was one of more than a half dozen “hub” settlements founded by the LDS Church in the nineteenth century. These hub communities were usually established in new or virgin territory or where Mormon influence was small. Once established, hub villages became the centers from which new villages could be built, radiating outward like the spokes of a wheel. They were, in short, outposts for church power. To be chosen or “called” to participate in these communities was an act of faith comparable and more enduring than any religious sacrament. By traveling south to St. George and becoming citizens of the new village, the Ivins family was on an errand for the Lord.

“You may pass through all the settlements,” said Apostle George A. Smith, “and you will find the history of them to be just about the same.”35 Elder Smith, who had a special responsibility for southern Utah and for whom the new village was named, might well have been speaking of the first months and years of St. George. According to one scholar, the process followed a pattern:

- The group went to the new settlement site after the fall harvest.

- Church officials selected or approved a president for the settlement, whom the settlers also voted to sustain.

- Settlers first worked on water systems, farmland preparations, community fortifications, and public buildings such as schools and meetinghouses.

- The next spring, settlers cultivated and planted crops and built fences to keep cattle out of the newly sown fields.

- That same year, surveyors laid out streets and lots for the town site, usually following or adapting the Salt Lake City pattern.

- Presiding officers in the community assigned house lots and farm plots.

- In the late spring and summer, settlers farmed in earnest, built houses, planted gardens.

- Settlers participated in Mormon wards that provided religious, educational, and social activities for the community.36

When Tony Ivins and his family arrived in Dixie, they had already participated in some of these stages of village building, and they would participate in still more. Along with the rest of the settlers, the Ivinses camped on land southeast from where the new village was intended. Here “East Spring” meandered, but the settlers deepened it with the same plow that turned the first furrow in the Salt Lake Valley. On both sides of this ditch the settlers placed wagons and tents, with Asa Calkin’s large Sibley tent serving as headquarters. For toilets, men went to the right and ladies to the left, the usual Mormon wagon train pattern.37

By the third week of December more than 700 people were in camp, and the settlers were already becoming involved in the routines of Mormon village life. An open-air Christmas dance was arranged for children in the afternoon, with another to follow in the evening for adults. Perhaps no activity was more quintessential of Mormon village life — certainly no recreation. Dancing united the people without distinction and was a passion.38 Unfortunately, just as the festivities began that Christmas day, it started to rain. However, the people refused to be deterred. “It began to rain and [we] began to dance, and we did dance, and it did rain,” remembered Robert Gardner.

We danced until dark, and then we fixed up a long tent, and we danced [some more]. The rain continued for three weeks, but we did not dance that long. We were united in everything we did in those days. We had no rich and no poor. Our teams and wagons and what was in them was all we had. We had all things in common and very common too.39

Israel’s call to Dixie came partly because of his special skills. Shortly after arriving he was appointed head of a six-man committee to remove water from the Virgin River for irrigation. Still more important, he was a surveyor. In January 1862, under the direction of the head of the colony, Erastus Snow, Israel began to chart the streets and lots of the city of St. George, and by the end of the year, he had completed a map of the new community.40 This was a job that young Tony could help do: “I was frequently with … [my father] while he was engaged in laying off the city and surveying the field lands,” he later wrote. As Israel continued to survey the Dixie area beyond St. George, it is likely that Tony remained at his side. We do know that when Brigham Young commissioned the building of the Washington cotton factory in the mid-1860s, Tony, then thirteen, manned one end of the surveyor’s chain. It was necessary to survey the surrounding land in order to bring water to the factory’s water wheel.41

This was the kind of work the boy enjoyed — being outdoors, doing men’s work, and helping to sustain the family. His enjoyment of the open air perhaps explains why Tony never confused schooling with education. His record as a pupil was short and spotty. During the winter of 1861 — when the rains were unremitting — Tony attended school in a tent on the old camp ground. While the girls were reportedly well mannered, some of the boys refused to be disciplined and left the tent at will. The next year, Tony and about ten classmates met in a structure made of willows; two large square openings served as windows, but, inexplicably, there was no door — at least that was Tony’s memory. The teacher’s desk was a packing box, while seats for the children were slabs of elm, “so high that their feet hardly reached the ground.” The students shared a single McGuffy’s reader, and two slates were passed around for writing.42

Perhaps by the third or fourth year, Tony had the advantage of going to school in one of the community’s first well-built structures. The St. George pioneers had commissioned a stone building (21 x 40 feet) a month after arriving, for “educational (school) and social (dancing and other recreation) purposes.” But, whatever their hope, it was several years before the community’s temporary shanties — dugouts, tents, willow lean-tos, and “made-do” wagon beds — began to give way to a more permanent landscape.

Schoolmarms and schoolmasters differed. Many students liked the slightly deaf Orphia Everett (she had “a profound regard for her students, and was proud of their success”).

Using the established pedagogy of her time, Everett refused to allow picture drawing on the children’s slates and had the children learn by “reading around.” When Everett’s home was torn down years later, a book from Tony was found among her keepsakes, perhaps a gift to her because of her influence.43 Richard S. Horne’s methods were more “scientific.” “We were not known by our names in his school, but by numbers,” Tony recalled. “My number was 12.” Horne’s regimen — and Tony’s attraction to the outdoors — apparently ended his formal schooling after several years at the primary level. He had been “going down and down until he left school,” reported a family friend.44 The reference was probably to Tony’s grades or attendance — maybe both.

There may have been a more basic reason for leaving school. “The first indispensable necessities of the pioneer are food to sustain his body [and] clothing with which to cover it,” Tony later wrote.45 Perhaps the boy left school to help out the family. Israel had entered into plural marriage before moving to St. George, and about the time that Tony left school, Israel brought Julia Hill and her child, Julia Ann, south. The enlarged household meant even more chores to do, including driving to the canyons for kindling, chopping wood for the family stove, and milking the cows. Tony’s chores also included driving the cows to pasture each morning and bringing them back in the evening. It was a task that the boy first completed on foot and then on horseback. (“From the time that my legs were long enough to reach across the back of a horse I was in the saddle.”)46

Herding was a job that left the boys unsupervised, and sometimes the result turned out badly. “Our heard [sic] boys are studying all kinds of vice, nearly without exception,” one concerned bishop said in Salt Lake City. “If he herds three months, he is then a perfect rascal.”47 In Tony’s case, he used his freedom on the range to mix with the local Shivwit Indian boys, which began a life-long fascination with Native Americans. From them, he learned how to make an Indian “bow of beautiful proportions,” with arrows to match. According to Tony’s son, in later years his father would sit before a slowly smouldering fire, “thrusting a crooked squaw bush branch in and out of the hot ashes” before it straightened. Then, using “the sinew from the loins of a venison and feathers from the wing of a hawk,” he attached feathers to the arrow.48 Tony’s “Indian skills” involved more than manufacturing. It was said that he learned to out-shoot many of his Shivwit tutors and that he used his new weapon to hunt rabbits and quail for the family’s table, sometimes with enough left over for neighbors.49

Tony was equally adept with a gun. According to one of his memories related late in life, he had done well even on his first “official” hunting trip — an excursion with his father and his uncle, Anthony Ivins. After his father had flushed two deer from a ravine. Tony and “Uncle Anthony” fired at the same time, and the first deer went down. Believing he had killed the animal, Uncle Anthony allowed the boy to shoot the second. But Tony had no question about his marksmanship and insisted that he had killed both. The ensuing dispute was settled by a study of the animals. Since the two hunters’ shotguns used different gauges and different shot, young Tony was able to verify his success.50

We have another testament to Tony’s skill — no less than the showman William “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Cody was escorting a party of English investors into the Arizona strip, south of St. George, and hired Tony as one of his guides. After watching his skill with a bow and rifle, the showman challenged Tony to shoot a silver dollar out of his hand at thirty feet. Tony did just that, and Cody, impressed with his aim and no doubt relieved because of it, offered him a job with the “Wild West Show” on the spot.51 While the incident took place after Tony reached manhood, it suggested a great deal about his activities as a youth.

One of the staples of Tony’s early days was the frequent visits of Aunt Rachel Grant and her son Heber — and the visits of Ivins family to the Grant home in Salt Lake City. Young Heber especially remembered the first time he and his mother went to St. George during the fall and winter of 1865–66. Tony, himself, drove them. For twelve-and-a-half days, the seasoned and self-assured thirteen-year-old navigated the “wonderfully bad roads.” The citified Heber, raised in urban Mormonism’s Salt Lake City, was in awe. “I looked upon him at that time as a man,” Heber recalled, “and he did a man’s work.” Not only could he manage a team and wagon, but upon reaching St. George, he and Heber went to the canyon to gather wood, which Tony then skillfully bundled and took home.52

More than a Dixie rural culture divided the two boys. Tony was four years older than Heber, and both of the boys, by personality, were “very positive characters.” Whatever the reason, the two often disagreed, and Anna and Rachel had to intervene to prevent the “flow of gore.”53 Amid the conflict, the two sisters retained their serenity. They agreed the boys were both “leading spirits,” who naturally wanted to be “boss.”54 They also assumed that their sons would outgrow their quarrels, which one incident may have helped along. When a man declared Heber a “sissy and no good” (city boys may not have been warmly received in St. George), Tony stood up for his cousin.

“Take that back, or you’ll get a good licking,” Tony said, knocking the man down and offering him more. The man quickly backed down.

According to Heber, it was not the last time that Tony bloodied a nose, for he “had no modesty about hitting back.”55

By the age of eighteen, Heber was taking another look at Tony, and was impressed. In fact, he questioned if he measured up to Tony’s standard. “It was just as natural for me to play second fiddle, figuratively speaking, to the superior judgment of my dear cousin as it was to eat,” Heber said of this stage of their relationship.56 But the admiration was not one-sided. As the men grew older, their respect became mutual and deepened, and in time they became confidants and best friends.

This was a time when boys in their middle teens were often at work. But the St. George economy offered few chances for a youth like Tony to find employment. One study found that less than ten percent of the Dixie boys between the ages of ten and fourteen had jobs. Even when the young men reached their late teens, almost half remained unemployed.57 With jobs hard to find, the teenager worked in the Pine Valley lumber camps, about thirty miles to the north. Still more wide-ranging, he became a teamster, running freight from Salt Lake City and doing at least one circuit into Montana.58 The profession had a way of toughening a driver, and Tony, at the very least, learned to be plainspoken and bold.

He remembered a run-in with a fellow driver, who carried a double-barrel shotgun to enforce his rule of the road. “He never was without it, and he was a terror wherever he went,” said Tony.

One day, when I was pulling up a grade, in the mud, after a rain storm, I saw the ears of his big mules flopping over the top of the hill, and when he came in sight about the first thing I noticed was the shotgun.… The etiquette of the road required him to turn out, [but] when our teams came close together [and] stopped[, h]e looked at me … and said, “Young man, are you going to get out and give me the road?” I said, “I can’t very well get out.” He said, “Do you know what I will do, if you don’t?” “No sir,” I said, “I don’t know … [but] if you will just pull your mules’ heads around a little, I will make my horses pull … out of the road if they can.”

Tony’s idea was a compromise, and each of the drivers gave up a part of the road in order for their wagons to pass. Later, the shotgun-toting teamster praised the steel-nerved, soft-spoken teenager, who had refused to be bullied and who had talked him into a draw.59

The celebration of the outdoor, athletic life — of being a rugged sportsman in the frontier West — were a part of U.S. culture at the time, whether Theodore Roosevelt’s Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1886), Owen Wister’s The Virginian (1902), or Zane Grey’s Riders of the Purple Sage (1912). Tony Ivins might well have been the prototype of these western heroes. His bow-shooting, his rifle-shooting, his herding, and his driving as a teamster were only the beginning. The young man boxed. He fished. He rode the range. As he grew older, he became a lawman and an expert stockman. Departing from his usual western ways, he was also the captain of his local baseball team. In Tony’s time it was a hardy game without softening body pads, masks, shin-guards, and mitts and gloves.60

There seemed something primordial or latent deep within him that called him to an active life; it just required an event or person to call it forth. When only five or six years of age, he remembered watching his father mold bullets for the Utah War and later return shoeless and ragged from his duty in the canyon. “How it inspired me with a desire to bear arms and learn their use,” he said.61 Or, he remembered walking with his father to the family field in Salt Lake City and hearing about the New Jersey Ivinses’ “fine horses and hounds.” Such times also allowed him to hear about his father’s experiences as an expert shot, hunter, and fisherman. “I very naturally, at a very early age formed a strong attachment for dogs and horses, and the out of doors,” he said. After watching Elder Wilford Woodruff catch a basket of fish on the Jordan River (Tony only got an occasional bite fishing beside him), he was convinced that fishing was an art that needed to be learned.62

When Tony traveled to St. George in 1861, there were similar epiphanies. He watched his father shoot a green head mallard as it flew overhead. This “wonderful” event left him with “an almost uncontrol[l]able desire to be able to do a similar thing.” While just outside of Fillmore, he watched James Andrus spur his mount into the herd of horses and cast a lariat over the head of one of the animals. “I marveled that it could be done, and my admiration for the man who could accomplish such a feat was boundless.” Although Tony later became “something of an expert” with the lariat himself, he believed he never equaled Andrus’s technique.63

The boy performed frontier tasks and by most accounts he did them well. His St. George neighbor and future wife, Elizabeth Snow, probably little exaggerated when she said that Tony “always carried off the honors in everything he did. He won all the prizes.”64 Another St. George citizen, Harold Bentley, called him “the top hunter and the top fisher.… He was good at everything.”65 However, Tony did not simply master the routines of frontier life; frontier life and especially his cowboy friends helped to make him what he became. “They were men of few words, these silent riders of the hills and plains,” he recounted. They were:

- Men of unsurpassed courage, but with tender hearts… where acts of mercy and service were required, as often was the case.

- Profoundly religious, they held in reverential respect the religions of others. Not many audible prayers were said by them, but when the day’s work was finished and the blankets spread down for the night, many silent petitions went up to the Throne of Grace in gratitude for blessings received.

“It was the example and teaching of such men … which left indelible impressions upon my mind.… These are some of the characteristics of this pioneer man which I so much admired: 1) He knew that other men found the Lord in temples built with hands just as he felt him near, here under the stars, 2) He was not a Pharisee, who magnified the faults of his fellowmen while blind to his own shortcomings, but one who, acknowledging his own imperfections, spread the mantle of charity over those of his neighbor.66

Other influences worked on the young man, too. Like his mother and especially his father, from whom he learned so much, he became “an avid reader of all books available.”67 He carried them in his saddle bags, and he read, among other times, as he fished, rode his horse, or drove a team. He liked travel books, American history and law, and books dealing with Native Americans. He also mentioned reading William Prescott’s six volumes on the Spanish conquest of Mexico and Peru. He later claimed that there was no mountain he had not climbed, no important river he had failed to cross, and no country he had not visited — all in books.68 This proxy touring was aided by his exceptional memory.

Nor was his bent for reading and culture solitary. In 1873, when twenty years old, Tony became a member of St. George’s Young Men’s Historical Club. Like youth self-help culture clubs elsewhere in the United States and in Mormon country (Salt Lake City’s more famous Wasatch Literary Society was not organized until 187469), the St. George group was started and run by the youth themselves and had a written constitution and by-laws.70 It met at the Fourth Ward social house on Friday evenings (later changed to Wednesday), devoted itself to debate and recitations, and issued a bi-weekly newspaper called the Debater. It is a “great blessing to all the members who attend,” said the St. George Enterprise. “Their efforts are praiseworthy.”71

At its peak, the Historical Club had twenty-five members, and it could have had more if the serious-minded young men had not precluded women — ladies were invited only to socials. One week after joining, Tony and his partner successfully debated the resolution “water had done more damage to Dixie than fire.” In later meetings, he delivered recitations (Catiline’s “Defense” and William Pitt’s reply to Sir Robert Walpole); readings (excerpts from Mark Twain’s Roughing It and Joseph Smith’s “History”); and lectures (topics included “the Pacific Slope,” “Mormon History,” “Scottish History,” and “the life and travels of Parley P. Pratt”). This was ambitious fare for a rural St. George youth, but Tony must have found the activities compelling. In addition to the club’s usual activity, he took time to edit the Debater. He also served several times as the club’s president.72

About the same time as his Historical Club activity, Tony joined the St. George Dramatic Society. With the exception of dancing, no recreation was more a part of Mormon village life than drama, which, like dancing, began in St. George almost from the outset of settlement. In 1862, Tony’s sister Caddie Ivins was among the first troupe of players; she created a sensation by appearing in the title role of “The Eton Boy” — in trousers. When Tony joined the company almost a decade later, some said that his motives had less to do with theater than with the handsome daughters of Southern Utah Mission President Erastus Snow, also players. Moreover, it was claimed that the young man was usually at his best when playing opposite one of them. Whatever his original motives, Tony became stage struck. In later years, he became one of St. George’s leading actors and a manager of its dramatic society.73

The Historical Club and the Dramatic Society suggested that as Tony began young manhood he had taken another path. One of his closest friends — a neighbor and school mate — also became a teamster. He found work in the mining town of Silver Reef, “learned to swear,” and followed the rough life of his teamster brothers — “two of the most profane men I ever knew,” said Tony. In effect, the three brothers exchanged Mormon St. George for the surrounding “wild and lawless” frontier, and, as a result, the body of one of the three was later returned to the village for burial. He had been killed in a scrap with another man. Less dramatic was the life of another of Tony’s friends. Tony and the boy grew up together, and for a time their interests were identical. There was nothing “wild” and “rough” in his character, Tony recalled. “We traveled together, we rode the range together; we went out for days and sometimes weeks together, sleeping under the same blankets.” Yet, as Tony’s religious faith began to mature, the other boy had no similar interest in the religion of his father and mother.74

Tony gave only a few details about his own stirring religious feeling, and none of these memories spoke of “going to meeting” as a young boy. Presumably, he did. In 1868, his mother Anna was called as the first president of the St. George women’s Relief Society and she served for almost two decades in various Relief Society leadership positions.75 Because of these activities and because of her unusual personality, she was one of the leading ladies in St. George, and Tony, a dutiful son, would have been expected to attend his meetings.

However, when Tony recalled the early spiritual events in his life, he talked less about church routines and more about the nurture of his neighbors. “These [tillers of the soil and silent riders of the hills and plains] were my teachers, the guardians of my youth,” he recalled. “They taught me, both by precept and example, that I must defraud no man, though the thing may be small. They taught me the fundamentals of integrity, industry, and economy. This is the heritage which the “Mormon” PIONEERS bequeathed to me, [and] all others who would receive their teaching.”76 In still another passage, he spoke of the “Saints of Christ” as “just simple folk … who are clothed in frailties … but who are striving to overcome[,] and thank the Lord are doing it.” For Tony, to be a part of this community and to do his daily duty was a “grand calling.”77 He was, of course, eulogizing the quiet values of a Mormon village.

The elders of St. George must have known Tony well. The home of Anna and Israel was on the southwest corner of First West and Second North Street, two blocks from the residence community leader Erastus Snow and an equal distance from the center of the town. The center square was where the Saints gathered for their dances and meetings and where they would build their tabernacle. Proximity seems to have worn well: church leaders called the young man to a series of LDS priesthood offices at an unusually early age. He was ordained an Elder at thirteen years of age and a Seventy shortly before he turned seventeen.78

A month after his nineteenth birthday, Patriarch William G. Perkins gave him a patriarchal blessing.79 Being admitted to the Mormon lay priesthood and receiving a prophetic blessing about his future sobered Tony. In a “modest sense,” he felt that was now a part of the Church, he concluded that he “could no longer be himself” and that “he could not talk as he had talked before”; he must “submerge himself in the Church.”80 Likewise, his patriarchal blessing “profoundly impressed” him with the need to prepare for the future.81 The young man’s faith was developing. He began to read the scriptures and church books and to pray. He even sought to convert a wayward chum. He understood that in the past he “had not been as careful to seek the Lord and honor him as I should have been.”82

As the boy came of age, Israel was often away. In the 1860s he surveyed several locations in southeast Nevada, and Brigham Young called him to survey southern Idaho and, after the passage of the homestead and preemption laws, to resurvey land near Salt Lake City.83 Then in the early 1870s, peripatetic Israel sought his bonanza in northern Utah’s mines.84 These activities lessened his profile in St. George and seemed also to reduce his role in Tony’s life. However, Anna’s influence remained constant. “She was a woman of remarkable character, kind, charitable, slow to anger and never speaking evil of anyone,” Tony said. “She had lived in plurality of wives, under very trying circumstances, but I never heard a word of complaint, never heard her speak an unkind word to a man, woman, or children … and all who were acquainted with her loved her.”85 Tony’s mention of plurality broke a taboo. While Israel’s two families lived in the same small St. George home, the physical arrangement did not translate into a close family tie. For some reason, he and his mother seldom spoke of Julia or her children.

By the time Tony reached his early twenties, much of what he was to become was in place. He stood 5 feet 10 inches and weighed a wiry 160 pounds.86 His finely-etched features suggested his northern Europe ancestors: thin eyebrows, a narrow nose, precise lips. He was a handsome man. However, beneath this genteel exterior, there was also a toughness that mixed with an easy-going manner. The combination made people like him. They recalled the “thrill” of watching him maneuver a horse at the roundups, how he carried a gun on a hunt, or his presence on the judges’ stand at the race track.87 One of his contemporaries recalled: “While yet a youth he had his horse races, his contests, his friendly rivalries,” yet he was known as “a square shooter, a real man. Most of the old-timers call[ed] him Tony.”88

This, then, was the beginning of one of Dixie’s leading men. The future held many roles: missionary, lawman, Indian friend, actor, stage manager, husband and father, cattleman on the Kaibab, politician, attorney, prosecutor, assessor and collector, mayor, churchman, and delegate to Utah’s constitutional convention. Dixie’s son would promote roads, education, and water management. Finally, he would serve as the leader of his church’s Mexican colonies, a member of the Quorum of Twelve Apostles, and as a counselor in the LDS First Presidency. Looking back on his life and on all activities that had ensued, he sensed the importance of the place where he had grown up. “My habits of life were, to a certain extent, forced upon me,” he said shortly before his death. “From my childhood I have lived upon the frontier.”89

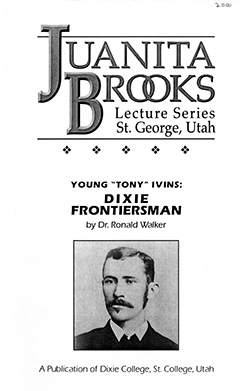

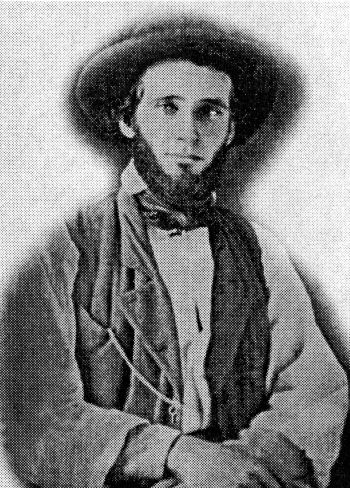

Young Tony Ivins, about age 10, shortly after the family’s move to Dixie

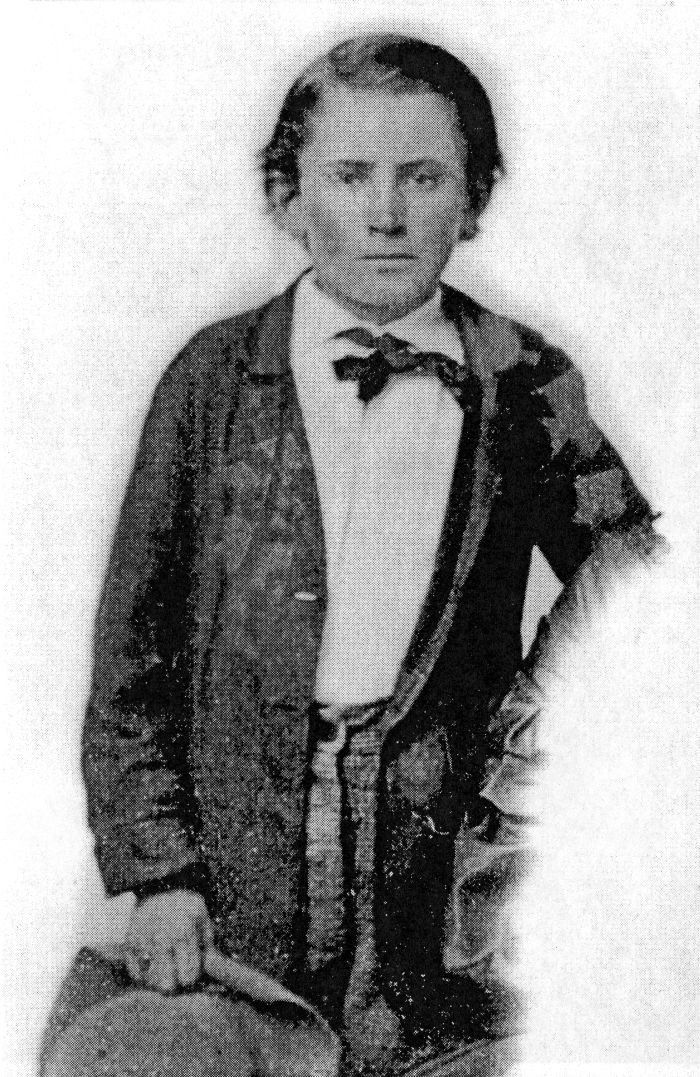

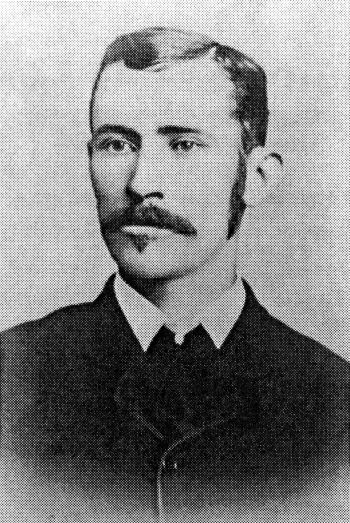

Antony Ivins in his late 20s, about the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Ashby Snow.

Tony Ivins as he began in the Young Men’s Historical Club & St. George Dramatic Society.

Israel Ivins (1815-1897) and Anna Lowrie Ivins (1816-1896), distant cousins, marriage partners, and parents of Anthony W. Ivins.

The St. George home of Anna and Israel Ivins where Tony grew up. On the southwest corner of First West and Second North streets.

Footnotes

- Anthony W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” typescript, Utah State Historical Society, Salt Lake City, Utah, [hereafter USHS], 3. Ivins’s autobiography took several forms, each with slightly different content. For the best single volume dealing with St. George history, see Douglas D. Alder and Karl F. Brooks, A History of Washington County: From Isolation to Destination, Utah Centennial County History Series (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society, 1996). This paper owes a warm debt to my researcher Bruce Lott, who helped not only with its research but also with preparing a preliminary draft.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 16.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 17.

- Job 5:26.

- Ivins family history and genealogy: Archibald F. Bennett, “Some Quaker Forefathers of President Ivins,” Utah Genealogical and Historical Magazine 22 (October 1931): 145-64. Ivins in Hornerstown: Franklin Ellis, History of Monmouth County, New Jersey (Philadelphia: R. T. Peck and Company, 1885), 633. Toms River: New Jersey Courier, September 28, 1934, and William H. Fischer to Heber J. Grant, November 9, 1934, box 150, folder 4, Heber J. Grant Papers, Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [hereafter LDS Library-Archives]. Paternal grandfather: A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 5. Family standing: John M. Horner to Heber J. Grant, November 7, 1906, box 37, folder 1, Grant Papers.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 5; Heber J. Grant, Conference Report, October 1934, 3.

- William Sharp, “The Latter-day Saints or ‘Mormons’ in New Jersey,” typescript of memo prepared in 1897, LDS Library-Archives. Sharp was preparing a history of New Jersey and drew upon local and now unavailable sources. His memo was sent by Elmer I. Hullsinory to Mr. Myers, Elizabeth, New Jersey to Salt Lake City on March 5, 1936; also see A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 3.

- Both the father and grandfather of Anna Ivins bore the name “Caleb.”

- Letter of Benjamin Winchester, July 7, 1838, in the Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints [hereafter JH], LDS Library-Archives.

- William Sharp, “The Latter-day Saints or ‘Mormons’ in New Jersey,” 3; Edwin Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties (Bayonne, NJ: E. Gardner and Son, 1890), 253; and Ellis, History of Monmouth County, 633; Stanley B. Kimball, “ ‘Nauvoo’ Found in Seven States,” Ensign 3 (April 1973): 23.

- Bennett, “Some Quaker Forefathers of President Ivins,” 145-64; History of Monmouth County, 636.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 3; Kimball S. Erdman, Israel Ivins: A Biography (n.p., 1969, 3, LDS Library-Archives; and Parley P. Pratt to Joseph Smith, Jr., November 22, 1839, Joseph Smith Papers, LDS Library Archives.

- Mary Grant Judd, Jedediah M. Grant (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1959), 62.

- Thirteenth Ward Relief Society Minutes, Book A: 1868-1898, February 11, 1897, 611, LDS Library-Archives and Charles Ivins to Brigham Young, July 1845, LDS Library-Archives.

- Andrew Karl Larson, Erastus Snow: The Life of a Missionary and Pioneer for the Early Mormon Church (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1971), 68.

- Mormon respectability: Salter, History of Monmouth and Ocean Counties, 253; disruption of worship: William R. Maps Diary, March 27, 1842, cited in History of Monmouth County, New Jersey, 640.

- Sharp, “The Latter-day Saints or ‘Mormons’ in New Jersey,” 2-3.

- Theodore McKean, “Autobiography,” 2, manuscript, LDS Library-Archives.

- “Interview with Heber J. Grant,” New Jersey Courier, November 9, 1934, clipping in the Heber J. Grant Papers, box 150, folder 4.

- Frances Bennett Jeppson, “With Joy Wend Your Way: The Life of Rachel Ivins Grant, My Great-Grandmother,” 9-10, manuscript, LDS Library-Archives.

- Brigham Young, Remarks, February 2,1862, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (Liverpool and London: Latter-day Saints Book Depot, 1854-86) 9:189.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 13-14.

- J. R. Kearl, Clayne L. Pope, and Larry T. Wimmer, “Household Wealth in a Settlement Economy: Utah, 1850-1870,” Journal of Economic History 40 (September 1980), 483-85 and Dean L. May, Three Frontiers: Family, Land, and Society in the American West, 1850-1900 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 295. In 1850 the mean wealth of Utah’s households was one-fifth of the national average ($201 to $1,001). Twenty years later the ratio had narrowed to a third of the national level ($644 to $1,782).

- Kearl, Pope, and Wimmer, “Household Wealth in a Settlement Economy,” 491-94; Larry Wayne Draper, “A Demographic Examination of Household Heads in Salt Lake City, Utah, 1850-1870,” M.A. Thesis, Department of History, Brigham Young University, 1988, 78-79.

- Charles S. Peterson, “Touch of the Mountain Sod”: How Land United and Divided Utahns, 1847-1985 (Ogden, Utah: Weber State College Press, 1989; Dello G. Dayton Memorial Lecture), 9.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 17.

- The extensive scholarly literature dealing with the Mormon village includes Reed H. Bradford, “A Mormon Village: A Study in Rural Social Organization,” (Ph.D. diss., Louisiana State University, 1939; Richard V. Francaviglia, The Mormon Landscape: Existence, Creation, and Perception of a Unique Image in the American West (New York: AMS Press, 1978); Richard H. Jackson, “The Mormon Village: Genesis and Antecedents of the City of Zion Plan,” Brigham Young University Studies 17, no. 2 (1977): 223-40; Richard H. Jackson and Robert L. Layton, “The Mormon Village: Analysis of a Settlement Type, Professional Geographer 28 (May 1976): 136-41; May, Three Frontiers; Lowry Nelson, The Mormon Village: A Study in Social Origins, Brigham Young University Studies, no. 3 (Provo, Utah: Research Division, Brigham Young University, 1930; and Ronald W. Walker, “Golden Memories: Remembering Life in a Mormon Village,” in Nearly Everything Imaginable: The Everyday Life of Utah’s Mormon Pioneers, Ronald W. Walker and Doris R. Dant, eds. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1999), 47-74.

- May, Three Frontiers, 162-63, 185, 227-30, and 259. While no study has been made of the economics of St. George, preliminary evidence suggests that the village fit this profile of marginal money-making. See Larry M. Logue, A Sermon in the Deseret: Belief and Behavior in Early St. George, Utah (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1988), 82-83, and 143-44.

- Nelson, Mormon Village, xiii.

- Elizabeth Snow Ivins, “Autobiography,” typescript, 1, USHS; also see Caroline Ivins Pace Diary, published in Erdman, 21-26.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 18.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 20.

- Elizabeth Snow Ivins, “Autobiography,” 3.

- Wayne L. Wahlquist, “Settlement Processes in the Mormon Core Area, 1847-1890,” Ph.D. diss., University of Nebraska, 1974), 93-95, 100.

- George A. Smith, Sermon, May 24, 1874, quoted in Church News, May 26, 1979.

- This list is adapted from John W. Reps, Cities of the American West: A History of Frontier Urban Planning (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1979), 313.

- A. R. Mortensen, ed., “Utah’s Dixie, the Cotton Mission,” Utah Historical Quarterly 29, no. 3, July 1961), 209.

- Larry V. Shumway, “Dancing the Buckles Off Their Shoes in Pioneer Utah,” in Nearly Everything Imaginable: The Everyday Life of Utah’s Mormon Pioneers, Ronald W. Walker and Doris R. Dant, eds. (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University Press, 1999), 195-221; Ronald W. Walker, “Golden Memories, Remembering Life in a Mormon Village,” in Nearly Everything Imaginable, 67-68.

- Mortensen, ed., “Utah’s Dixie,” 209. Another pioneer remembered that the dances were suspended, although a downsized version was later held in Calkin’s tent. See Ruth M. Pickett Washington, “First Christmas in St. George,” Treasures of Pioneer History, Kate Carter, comp., 6 vols. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1952-1957), 1:116.

- Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 7; James G. Bleak, Annals of the Southern Utah Mission, Book A, 1870, 73, 92, manuscript, LDS Library-Archives; A. W Ivins, “Autobiography,” 21-22; Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 7, USHS; Erdman, Israel Ivins, 27; and Stanley S. Ivins, ed., “Journal of Anthony W. Ivins,” typescript, 2, LDS Library-Archives.

- Stanley S. Ivins, ed. Journal of Anthony W. Ivins, LDS Library-Archives, 2; Heber J Grant, quoted in Joseph Anderson, Prophets I Have Known (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company, 1973), 68.

- Anthony W. Ivins, “Journal,” USHS, 1:8; Anthony W. and Elizabeth S. Ivins, “Reminiscence,” September 16, 1934, typescript, USHS, 2; Charles W. Skidmore, “Dedicatory Address at the Monument Erected on Dixie College Commons, In Honor of Anthony W. Ivins and Edward H. Snow,” typescript, LDS Library-Archives, 1.

- Josephine J. Mills, “Washington County, Heart Throbs of the West,” Kate B. Carter, ed. 12 vols. (Salt Lake City, Utah: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1939-1951): 12:39.

- Anthony W. and Elizabeth S. Ivins, Reminiscence, 2; Salt Lake Telegram, September 24, 1934, 7; Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 19; Harold W. Bentley, “Oral History” (1978), 15, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, Harold B. Lee Library Special Collections, Brigham Young University.

- Anthony W. Ivins, “Design for Living,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 24, 1934, 1.

- Anthony W. Ivins, Address delivered upon Completion of the Union Pacific Lodge at Grand Canyon, Utah, [September 15, 1928] (Salt Lake City, Utah: Union Pacific System, 1935), 3, copy in Ivins Papers, USHS; Stanley S. Ivins, “Anthony W. Ivins: Boyhood,” Instructor 78 (November 1943) 569; cf. A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:8.

- Edwin D. Woolley, Remarks, November 6, 1855, Record of Bishops Meetings, Reports of Wards, Ordinations, Instructions, and General Proceedings of the Bishops and Lesser Priesthood, 1851 to 1862 [Salt Lake City], LDS Library-Archives.

- Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 10.

- Outdoing the Shivwits: Heber J. Grant, Address at the Utah Agricultural College Founder’s Day Exercises, March 11, 1936, Logan, Utah, 5, text in Heber J. Grant Letterbooks, 83:14, LDS Library-Archives; Heber J. Grant, Sketch Introducing Anthony W. Ivins, Grant Letterbooks, 67:32; and Anderson, Prophets I Have Known, 67. Dinner fare: Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 10; A. W. Ivins “Journal,” 1:8; and Koller, “Son of Saintland,” 24.

The hunting incident had a sequel, which gave it special meaning. Another of Israel’s brothers, Thomas Ivins, visiting from New Jersey, at the last minute had dropped out of the hunting party because he doubted its success. When told of Tony’s exploit, he was incredulous. “If there is a deer in that wagon I will give the man that killed it fifty dollars,” he said. When Thomas saw the kill, he praised Tony but gave no money. However, after Thomas returned to New Jersey, he mailed the $50, which, according to Tony, had an important impact on his life. “There were many things I needed,” Tony said. “I wanted a new saddle, as much as anything else, but I finally gave it to a prospector for a part interest in a mine he had discovered in the Tintic [mining] district. That district was then just being prospected.

Later, I traded my interest in the mine for a city block [in St. George]. I developed this block, planted a vineyard on it and some time later sold it for $500. I bought another lot upon which my home stood in St. George and where [my family] lived continuously for 15 years after marriage.” A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:5-6, 12-15 and as quoted in the Deseret News, Special Section, September 1934. Also see Stanley S. Ivins, “Boyhood,” 568-69.

- Koller, “Tony Ivins — Son of Saintland,” 49. For Cody’s tour of the area, see Angus M. Woodbury, “A History of Southern Utah and its National Parks,” Utah Historical Quarterly 12 July-October 1944), 190-91.

- Heber J. Grant, Address at the Utah Agricultural College Founder’s Day Exercises, 1.

- Heber J. Grant to Anthony W. Ivins, April 6, 1904, Grant Letterbooks 38:522-24; Heber J. Grant to Junius F. Wells, April 14, 1921, Grant Letterbooks 57:813.

- Lucy Grant Cannon, “A Few Memories of Grandma Grant,” 8, manuscript, LDS Library-Archives.

- Heber J. Grant, Address at the Utah Agricultural College Founder’s Day Exercises, 4.

- Heber J. Grant to Junius F. Wells, April 14, 1921, Grant Letterbooks 57:813.

- Logue, Sermon in the Desert, 83.

- Stanley S. Ivins, ed., “Journal of Anthony W. Ivins,” 22.

- Anthony W. Ivins, Conference Report, October 1916, 67.

- Elizabeth Snow Ivins, “Autobiography,” 2, and Heber J. Grant, in Anderson, Prophets I Have Known, 69.

- A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:5-7.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 14-15.

- A. W. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 18-19.

- Elizabeth Snow Ivins, “Autobiography,” 2.

- Harold W. Bentley, Oral History, 15, Charles Redd Center for Western Studies, 1978, Brigham Young University Special Collections.

- Ivins, Address Delivered upon Completion of the Union Pacific Lodge 7, 9-10.

- Heber Grant Ivins, “Autobiography,” 19. Heber J. Grant considered Anna a “student,” apparently because of reading, see Heber J. Grant, Conference Report, October 1934, 3.

- Anderson, Prophets I Have Known, 67; Charles Foster, quoted in Salt Lake Telegram, September 24, 1934, 7; Koller, “Son of Saintland,” 25; and Heber J. Grant, Sketch Introducing Anthony W. Ivins, Grant Letterbooks, 67:32.

- Ronald W. Walker, “Growing Up in Early Utah: The Wasatch Literary Association, 1874-1878,” Sunstone 6 (November/December 1981): 44-51.

- Record of the Young Men’s Historical Club, typescript, USHS.

- St George Enterprise, March 8, 1874, 1.

- Young Men’s Historical Club, transcript.

- “Culture in Dixie,” Utah Historical Quarterly 29 (1961): 263; Zaidee W. Miles, “St. George Footlights,” paper presented to the Daughters of the Utah Pioneers at St. George, 1923, typescript, USHS; “Life Sketch of A. W. Ivins,” no date, typescript, LDS Library-Archives; Alder and Brooks, A History of Washington County, 165-166; John Taylor Woodbury, Vermillion Cliffs: Reminiscences of Utah’s Dixie (St. George: The Woodbury Children, 1933), 49.

- Anthony W. Ivins, Conference Report, October 1919, 175, 177.

- The details of Anna’s selection suggest the esteem with which she was held by her neighbors. She was chosen by the women themselves and not by a “calling” extended from local church leaders. James G. Bleak, Annals of the Dixie Mission, August 24, 1868, 296. Woman’s Exponent, February 15, 1896, 116, states that Anna served as the Stake President of the St. George Relief Society for twenty years. Another source suggests that for a period of time, Anna was a counselor in the presidency, see Verna L. Dewsnup and Katharine M. Larson, comp., Relief Society Memories: A History of Relief Society in St. George Stake, 1867-1956 (Springville, Utah: St. George Stake Relief Society, 1956), 1-3.

- Anthony W. Ivins, “Pioneers,” Improvement Era 34 (September 1931): 637-40, 672-73.

- Anthony W. Ivins to W. H. Ivins, June 8, 1905, Heber J. Grant Letterbooks 39:960.

- Andrew Jenson, Latter-day Saint Biographical Encyclopedia, 4 vols. (Salt Lake City: Andrew Jenson History Company, 1901-1936) 3:750; A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:198.

- A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:17-19.

- A. W. Ivins, Remarks, General Priesthood Meeting, April 7, 1934, in General Correspondence, Heber J. Grant Papers, box 85, folder 20, LDS Library-Archives.

- A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:17.

- Ivins, Conference Report, October 1919, 177; A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:19.

- Heber G. Ivins, “Autobiography,” 8; A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:10.

- A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:10-11.

- A. W. Ivins, “Journal,” 1:243. Heber J. Grant shared the judgment: “I have said time and again that of all the women I ever knew, Brother Ivins’ mother and my own seemed to be possessed of the most perfect and serene temperaments. If anything, I would give Aunt Anna Ivins the credit for having the more serene character of the two, and that is saying a whole lot.” Heber J. Grant, Remarks at Birthday Celebration, no date, typescript, box 177, folder 8, Grant Papers.

- David Dryden, Biographical Essays on Three General Authorities of the Early Twentieth Century: Anthony W. Ivins, George F. Richards, and Stephen L Richards, Task Papers in L.D.S. History no. 11 (Salt Lake City, Utah: History Division, Historical Department of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1976), 1.

- “Character Sketch of A. W. Ivins,” 3-4.

- The Daily Leader [Brigham Young University], January 28, 1925, 1-2, clipping, Ivins Collection, LDS Library-Archives.

- Ivins, “Design for Living,” Salt Lake Telegram, September 24, 1934, 1.