The Juanita Brooks Lecture Series

The 24th Annual Lecture

Utah’s Dixie: A View from Across the Cultural Divide

by W. Paul Reeve, Assistant Professor, University of Utah – Salt Lake City, UT

St. George Tabernacle

March 14, 2007

7:00 P.M.

Co-sponsored by Val Browning Library, Dixie State College

St.

George, Utah

and the Obert C. Tanner Foundation

About Juanita Brooks

Juanita Brooks was a professor at [then] Dixie College for many years and became a well-known author.

She is recognized, by scholarly consent, to be one of Utah’s and Mormondom’s most eminent historians. Her total honesty, unwavering courage, and perceptive interpretation of fact set more stringent standards of scholarship for her fellow historians to emulate. Dr. Obert C. and Grace Tanner had been life-long friends of Mrs. Brooks and it was their wish to perpetuate her name through this lecture series. Dixie State College and the Brooks family express their thanks to the Tanner Family.

About the author

W. Paul Reeve grew up in the small southern Utah town of Hurricane. His ancestors were sent to Utah’s Dixie in 1861 as a part of the Cotton Mission and portions of his family have been there ever since. His father raised beef cattle on the Arizona Strip, so his youth was filled with horse riding, branding, irrigating, and manure.

Reeves holds a BA and MA in history from Brigham Young University and a PhD in history from the University of Utah. At the U, he studied under Dean L. May and was May’s last doctoral student to graduate before May’s untimely death in 2003. Reeve’s first full-time teaching position was at Southern Virginia University in Buena Vista, VA. While there, he enjoyed taking students to Monticello, Jamestown, and Colonial Williamsburg, as well as going camping with his family in the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In 2005 the University of Utah hired Reeve to teach Utah history and the history of the American West — the position held by his mentor, Dean May. He feels honored to be at the U and to follow in May’s footsteps. His first book Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes, a revision of his award-winning dissertation, will be published in March 2007 by the University of Illinois Press.

Reeve currently serves on the advisory board of editors for the Utah Historical Quarterly and on the local advisory council for the Museum of Utah Art and History. He was awarded a Mayers Research Fellowship at the Tanner Humanities Center at the University of Utah for fall 2007. He will be researching nineteenth-century notions of Mormon physical otherness.

Reeve is married to Beth Brumer and they are the parents of four wonderful children — Porter (age 8), Eliza (age 6), Emma (age 4), and Hunter (age 18 months). As if four children were not enough, the family also adopted a poodle last year, whom Porter promptly name Buck, after the dog in Call of the Wild. Amidst the chaos of raising four kids and a poodle, the Reeves enjoy reading, hiking, sledding, camping, soccer, art, and gymnastics.

Utah’s Dixie: A View from Across the Cultural Divide

I am deeply honored to be invited to give the Juanita Brooks lecture. I have been an admirer of Juanita Brooks since the time I first read Mountain Meadows Massacre as a history major at BYU about fifteen years ago. I still stand in awe of her courage to tell southern Utah’s ugliest story and to shed light on Mormonism’s darkest hour. It is impossible to research southern-Utah history without bumping into traces of Juanita Brooks. She left a lasting legacy upon southern Utah historiography and all of those who rummage through the Dixie past are in her debt. My encounters with her are always pleasant and have come to be almost reverential so that to be asked to deliver the lecture named in her honor is at once daunting and thrilling. I will always cherish the privilege that Dr. Alder and the community have given me tonight.1

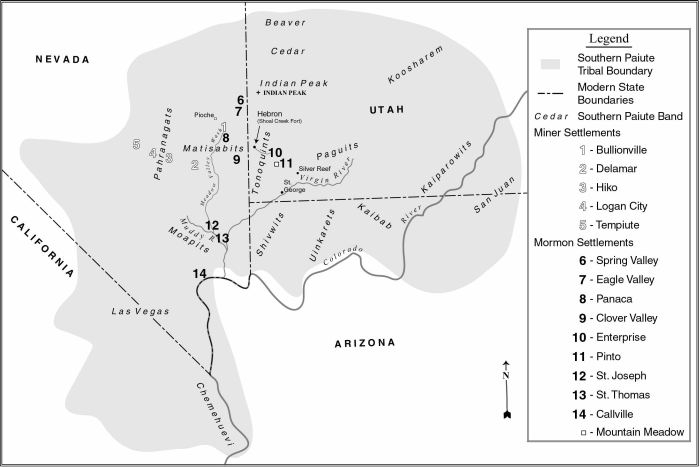

It was in July 1869, that Erastus Snow, Mormon apostle and leader of Mormon settlement in southern Utah, toured the fringe settlements of the Cotton Mission in southwestern Utah and southeastern Nevada. His trip took him to Hebron, Clover Valley, Panaca, Eagle Valley, and Spring Valley, a string of ranching outposts that in the words of Snow formed a “frontier line,” close to the mines of soon to be named Pioche, Nevada. Snow recorded his assessment of the region in a letter to Brigham Young, noting that “notwithstanding their proximity to the mines and a periodical influx of adventurers, the people, generally, with a few exceptions seem to be striving to live their religion.” Nonetheless, Snow perceived that these folk of the fringe were vulnerable and advised that they “need the watch care of a . . . thorough and efficient man.” That man, Snow clarified, should be someone who had “a little knowledge of law as well as gospel” and more importantly, someone who possessed “practical sense and wisdom to hold in check outside influences.”2

Although it is not clear that Snow ever found his man, it is apparent that the policy he dictated—“to hold in check outside influences”—came to characterize the nature of Mormon settlement in southern Nevada and Utah. Mormons there spent much of their nineteenth-century existence posturing defensively against miners at Pioche and Silver Reef.

Historians have primarily focused upon the Mormon capital as the site where outside influences eroded Zion’s communitarian space, thereby dragging Utah into mainstream American political, economic, and social worlds by the end of the nineteenth century. Even Mormon leaders perceived a corrosive force at work in Salt Lake City. In 1865 Heber C. Kimball, first counselor to Brigham Young, declared to a Centerville, Utah, congregation: “I admit that the people are better in the country towns than in Great Salt Lake City, for the froth and scum of hell seem to concentrate there, and those who live in the City have to come in contact with it; and with persons who mingle with robbers, and liars, and thieves, and with whores and whore-masters, etc.”3 Even though Salt Lake City bore the brunt of the gentile impact, the contest over Zion’s soul also engulfed Utah’s southwestern frontier. In fact, due to the physical separation of gentile and Mormon towns, southern Utah leaders could more clearly draw lines meant to divorce their perceptions of the good from the evil.

Mormons attempted to defend those lines on a variety of levels, political, social, geographic, and economic. Initially the battle raged geopolitical, as frontier saints jostled with miners over land and resources in the wake of silver discoveries at Pioche in the late 1860s and then at Silver Reef which was founded in 1876. However, as these mining camps rapidly assumed regional economic importance, the contest over land for the Mormons devolved into an effort to resolve conflicting temporal and spiritual concerns. The saints struggled to define the terms of their contact with Pioche and Silver Reef; many of the faithful, including Brigham Young, cuddled with those towns economically while declaring themselves spiritually repulsed. It was a problem that southern Utah Mormons learned to live with, but never fully resolved.

Miners also grappled with inconsistency in their views toward their Mormon neighbors. They generally looked across the cultural divide at the Mormons and noticed striking differences, most of which they described as un-American. In general they perceived themselves as the true guardians of American destiny and progress and the Mormons as barriers standing in their way. Miners denigrated Mormons for their general policy against mining for precious metals, for a perceived blind following of “priestly rule,” for their complicity in the Mountain Meadows Massacre, and for polygamy.

The stage was thus set for intercultural conflict. At odds was the primary purpose for which each group had come to the southern rim of the Great Basin in the first place. Both groups were in southern Utah seeking very different Gods through very different means. Mormons were building a geographic, economic, political, and ultimately religious kingdom, while the miners were seeking riches and advancing industrial civilization. The Mormons viewed agriculture as a stable way of life, while the miners saw the smelter and quartz mill as symbols of America’s industrial progress. The Mormons were building permanent homes in southern Utah, while the miners would stay only as long as the silver lasted. Mormons and miners thus wrestled with each other and with themselves as they attempted to define and defend starkly different ideals about what it meant to be an American in the last half of the nineteenth century.4

Mormon view of Miners and Mining

On the geopolitical front, the saints sought to outmaneuver the miners and claim the best land for Zion. Throughout the 1860s Mormons felt uneasy about miners prospecting in the region, a concern that only grew when in 1869 prospectors flooded into Meadow Valley and shortly founded Pioche.5 One Mormon soon grew uneasy, noting that “the Panaca mining district is considerably agitated at the present time; the miners are coming in very fast. They think there will be five thousand men in the mines this summer. Some of them talk of jumping land in the Valley.”6 By the end of 1869 Cotton Mission secretary James Bleak summed the saints’ apprehension this way: “This year activity in mining at Pioche has caused numerous companies of miners to look with greed on Meadow Valley. They acted in a very lawless manner, frequently threatening to dispossess the actual settlers, and otherwise deporting themselves in an offensive manner.” To make matters worse, the miners not only poured into Pioche, but also founded Bullionville, a mill town just a mile outside of Panaca.7 No wonder Erastus Snow brooded over the area and wondered how best to hold it.8

Eventually settlers at the outposts seemed to resign themselves to the fact that Pioche was there to stay. Erastus Snow even made peace with the idea. He visited Pioche in 1872, met with William Raymond and John Ely, two of the town’s largest mine owners, and according to Mormon accounts was treated “very kindly.”9 Nonetheless, Snow returned to St. George and continued to paint the raucous camp darkly. In essence, southern-Utah Mormons worked out a defense filled with inconsistency. Economically they enthusiastically embraced Pioche; spiritually, however, they viewed it as a threat to Zion, the very embodiment of a modern-day Babylon.

Brigham Young’s mining policy, replete with contradictions of its own, no doubt lay at the heart of the frontier settlers’ stance. Broadly speaking, it was a matter of control, an important distinction in understanding Young’s anti-mining stance. It was not so much the act of mining that Young disliked, as it was the individualism, instability, and social stratification that the search for wealth tended to breed. The boom and bust cycle of mining also deterred him. He was building a permanent home for his flock and needed sustainable and reliable resources. As long as mining operations existed for the benefit of Zion and could be managed on the cooperative plan, Young approved. Erastus Snow explained the distinction this way: “If the mines must be worked, it is better for the saints to work them than for others to do it, but we have all the time prayed that the Lord would shut up the mines. It is better for us to live in peace and good order, and to raise wheat, corn, potatoes and fruit, than to suffer the evils of a mining life.”10

Thus, it was easy for Young and other leaders to assign Pioche and Silver Reef spots in the Devil’s kingdom and begin defending Zion on spiritual grounds. At the Mormon town of Eagle Valley in 1865, Snow told the settlers that “he wished any man that would go to the Western mines as a miner to be cut off the church.”11 In 1868 local authorities informed Hebronites that trading with non-Mormons would be considered a “matter of fellowship.”12 Three years later at the groundbreaking ceremony for the St. George temple, Young’s counselor George A. Smith prayed God to pour out his wrath upon the enemies of the saints and to “overrule the discovery of minerals in this land for the good of thy people.”13

In 1873, Young returned to St. George to reinforce his message at the height of the Pioche bonanza. Annual bullion output had peaked at over five million dollars the previous year, and would reach nearly four million dollars in 1873. Population estimates for Pioche run as high as ten thousand people during those boom years, but more realistic guesses place the number at between four and five thousand. Even at that many, Pioche would have been home to more residents than all the Mormon settlements in Washington County combined. Clearly, not only its wealth and population, but its reported seventy-two saloons and thirty-two houses of prostitution, stood as ominous threats to Mormon values.14

Such notions must have weighed heavily upon Young in 1873. Concern over Pioche permeated his messages to Dixie saints that year. He “deprecated the desire of many to go to the mines and mingle with the wicked,—learn to swear—drink—gamble, lie and practice every other wickedness of the world.” He lamented that “the desire to make money caused many to forget the object of our mission on the Earth—which is the salvation of the living and the dead. Many were becoming lukewarm,” Young warned, “and, unless they repent, will have to be cut off the Church.”15 It was a principle upon which Young refused to relent. In 1877, the year he died, he preached what had become a familiar theme to his Dixie flock, this time also aimed at the new mining town of Silver Reef. At the dedication of the St. George Temple he urged the saints to “go to work and let these holes in the ground alone, and let the Gentiles alone, who would destroy us if they had the power.” “You will go to hell, lots of you, unless you repent,” he announced.16

He largely left it to local leaders to translate his rhetoric into action, a task that proved troublesome given the frontier location of their spiritual ground. Their defense largely coincided with Young’s notions of economic self sufficiency and an avoidance of trade with gentiles. Yet the abundance of work available at the mining camps and the allure of cash payments in a near-cashless economy pitted dogma against economic necessity. It forced settlers at the outposts closest to Pioche to enforce the speechifying through disfellowshipment and excommunication.17

In August 1868, ecclesiastical leaders at Hebron met to decide the fate of a family which had strayed, quite literally, from the Mormon flock. Erastus Snow presided at the gathering and under his direction the Hebron congregation decided to “cut off” Lucinda Jane Crow from the LDS church. Apostle Snow and the Hebron congregation excommunicated Lucinda Jane “for leaving her husband and the society of the Saints and choosing to live with the wicked at a gentile camp.” At that same meeting Benjamin Brown Crow, Lucinda’s husband, not only lost his wife to the gentiles, but was also “suspended from fellowship” with the saints. Such would be the case “until he makes satisfaction, for moving his family away from the gathering place and exposing them to be overcome in society of the wicked.”

Crow had moved his family from Hebron to Meadow Valley and located his new home near a sawmill “erected by outsiders” from the Pahranagat mining district in Nevada. One of the mill hands soon became a frequenter at the Crow home, and in the process employed “soft oily, low whispered words” to seduce Lucinda away “from home and from God.” Three months later, no doubt humbled by the loss of his wife and his fellowship in the LDS church, Crow returned to Hebron and made public confession. He expressed his sorrow for the course he had taken and declared his determination to be a Saint. Hebronites restored him to fellowship by a unanimous vote. As for Lucinda Jane, it seems her relationship with the “ill-favored gentile” did not last. Less than a year later she returned to friends in southern Utah, “in agony of mind, reaping the rich harvest of sorrow she had sown with her ‘manly beauty of a gentile’ in the distance.”18

According to one miner, other Latter-day Saints also moved to the mining camps in eastern Nevada: “Quite a number of families from the Mormon settlements have gone in and settled on lands there,” the prospector wrote, “and many more contemplate going in, early in the spring. Most of them . . . are apostate mormons; they consider it a fine chance to divest themselves from Brigham’s power.”19 Thus, whether fleeing on their own accord or being forced out, mining involvement became a test for some of their commitment to the Mormon cause.

Miners’ View of Mormon Stance Against Mining

As the miners saw it, Brigham Young’s outspoken policy against mining stood as an affront to the value systems at Pioche and Silver Reef and placed the Saints outside of prevailing American norms. Miners and government officials alike were clearly aware of the Mormon policy against mining, which became a fundamental barrier between the two cultures. Miner Stephen Sherwood, a founder of the Meadow Valley mining district, described feeling “unsafe” as a prospector, because he believed that “the Mormons were opposed to opening mines.”20 United States mining commissioner Rossiter W. Raymond claimed that “few” Mormons were willing to work as miners, and government surveyor George Wheeler noted that “the Policy of the Mormons has been to discourage mining.”21 The miners at Silver Reef were also aware of Young’s stance against mining and reported that on one occasion Young called the mines there “a delusion and a snare,” and predicted “that more money would be expended on them than there would be derived from them, and that Gentiles before long would be tired of them.”22

Some miners at Silver Reef even believed that the Mormons had known about silver there for sometime, but refused to develop it, insisting that the “mines would be opened when the Lord’s own time should come.” In response the Salt Lake Tribune suggested that outsiders had “‘brought the time” with them—“that Christ was too slow.’” “All concede,” the Tribune argued, “that the right time is now, and Saint and sinner alike are gobbling up all they can of it, and many of them are getting well heeled, as the shipments of ore abundantly show.”23

William Tecumseh Barbee, the primary promoter of silver in southern Utah, even argued that the mines at Silver Reef would prove a benefit to southern Utah saints. “Our Mormon friends are getting considerably excited about mines,” he wrote in 1875, “and are highly elated at the success attending our efforts to develop the mineral resources of the country. They have a hard time serving the Lord in this desolate, god-forsaken looking country,” he explained, “and it is about time for something to turn up to take the place of sorghum and wine as a circulating medium.”24 Another prospector from Utah’s Dixie even gave a “Hurrah” for the “hardy miners” of Silver Reef “who braved the Prophet’s bowie-knife and laid the foundations for a prosperous Gentile community in Southern Zion! We hope they will use Brigham’s new temple for a smelter,” he prodded.25

Mormon Interdependence

The irony of these opposing positions on mining is how much peoples from both groups came to rely upon each other for survival. From 1875 to 1908 miners at Silver Reef extracted an estimated $7.9 million worth of silver from that district and Pioche produced over $9 million worth of silver in its two peak production years alone. This influx of hard cash into a cash-poor Mormon economy was vital to the stability of the agricultural settlements. Silver Reef and Pioche provided a ready market for Mormon wine, fruit, beef, and grain and offered labor opportunities otherwise not available for teamsters, sawmill operators, carpenters, lumbermen, merchants, and miners alike. Similarly, Pioche and Silver Reef, no matter how much they resented it, came to rely upon Mormon traders for food and Mormon teamsters and sawmill operators for timber and labor.26

Even Erastus Snow and Brigham Young became economically involved at Pioche. In May 1871, Erastus Snow held a meeting at his home at St. George with some of the leading business and religious leaders of the region. The gathering was designed to establish “the best method to regulate the trade of vegetables, fruit and grain to Pioche.” Estimates among the assembled brethren suggested that southern Utah saints could peddle “three tons of vegetables, fruit, and grain per week” at the mining town. The goal was to direct and control this trade. In accordance, they organized the “Dixie Cooperative Produce Company,” and then assigned each southern Utah town a trade quota and a specified day of the week upon which residents could peddle their goods. Clearly for Erastus Snow, Mormon commerce at Pioche was not the issue; who controlled it was. Snow desired that the trade be conducted in a way that benefited all who had a surplus to sell.27

For the Dixie Cooperative, however, things did not work out as hoped. Bishop J. T. Willis of Toquerville chafed under the attempt to channel Pioche trade through the produce company. His protest killed the cooperative in its infancy. In July, peddlers from Toquerville violated their quota of one load per week, assigned to arrive on Tuesdays. Three Toquerville men had taken loads of fruit to Pioche in the same week and disrupted the established pattern. Agents of the Dixie Produce Company wrote to Bishop Willis and castigated him for the violation. They even warned Willis that failure to comply with company regulations was a matter of LDS church fellowship.

Such a rebuke enraged the bishop. Snow himself, Willis said, refused to make compliance with the company’s regulations a test of fellowship. More to the point, Willis questioned the very principles of the company and its harmful effects upon Toquerville’s ability to subsist: “You have an agent in Pioche, and say that our place is entitled to send one load a week,” he seethed. “Why gentlemen, the people here should doff their hats, for such extended liberality and generosity. One load a week!! Only think of it.” Even more sardonic, Willis continued: “Gentlemen, we thank you. By your proscription, our hard earnings must rot on the ground and the people reduced to the utmost state of destitution. Are we living in the dark ages?” he wondered. Willis vowed to bring the company’s “insolent note” before Erastus Snow, where it seems that the determined bishop’s plea for free enterprise won. Snow soon abandoned his attempt to control Mormon trade at Pioche and returned to rhetorical defenses against the iniquitous camp.28

Brigham Young, on the other hand, had better luck at the mining town. In June 1871 he made plans to extend a line of the LDS church owned Deseret Telegraph Company to Pioche. He hoped that “when completed it will soon pay for itself.” By October Mormon workers finished the line, and Young’s wish quickly came true. In 1868 gross receipts in tolls for the company had totaled a mere $8,400. By 1873, however, the company’s receipts had jumped to over $75,000; the Pioche office alone accounted for almost forty-five percent of that total.29

On a local level similar paradox characterized settlers’ relationships with Pioche. Many Mormons freighted and traded at the mining camp, all the while denouncing the evil that it embodied.30 Hebron resident Orson Huntsman wrote: “I made several trips to Pioche with lumber, in company with Father Terry and others from our place. Pioche proved to be a great camp, . . . [and] made a good market for lumber and other products or produce, also a great amount of labor. Bullionville was also a place of great note.”31 Over the next several years Huntsman continued his forays to Pioche and Bullionville. He generally returned home well pleased with his cash payments, especially after one trip where he sold “one little horse” for fifty dollars in gold.32 Despite the economic benefit, Huntsman still described Pioche as “a very wicked city,” or, “at least,” he explained, “there is some very wicked men and women in and around Pioche.”33

Hebronite John Pulsipher seemed to agree. In 1875, when work at the mines slowed, Puslipher used the economic downturn as proof of the division between the Kingdom of God and that of the devil: “Business is rather dull, money scarce, not much out side business going on. Clover Valley is being deserted . . . .[the people there] have depended on hauling lumber or other services of gentiles and [are now] out of employment and are moving back into our territory as poor as when they commenced work for unbelievers. . . . This is about the history of all that have a mission and calling in the kingdom of God and go to get rich building up the Devil’s kingdom.”34

Miner Interdependence

Just like the Mormons, miners at Pioche and Silver Reef had opportunities of their own to formulate opinions of their LDS neighbors, likely on a daily basis. As Mormons from throughout central and southern Utah freighted and traded at the mining camps it was easy for the miners to look down upon them.

The perception that perhaps the trade at Pioche was controlled by Brigham Young to fatten his coffers no doubt created resentment. “Thousands of dollars of gold and silver coin pass every month from Pioche to the Utah settlements, never to return,” the Pioche Daily Record complained in 1873. Thus the town’s hard currency was “lost to local circulation forever, and goes to swell the capital of that monopolizing institution of Brigham Young.” A report from Silver Reef in 1877 seemed to echo this concern. It described the Mormon apostles passing through the area on their way to St. George for a conference and focused upon their apparent wealth and status: They were “not dressed as were the ‘Apostles’ of old with sandals and gowns and wading knee deep through the sandy deserts, none of them hungry or thirsty; on the contrary, they came along in style, riding through Leeds in seven carriages, drawn by blooded stock. They look fat and slick, dressed up in the good, old-fashioned farmer style, and if their saintly noses do not belie them Dixie wine tells its tale.”35

The miners’ resentment notwithstanding, the arrival of “teams from Mormondom” became a fact of life at both Pioche and Silver Reef and continued well past the turn of the century.36 The miners, therefore, found ways to cope. At Silver Reef the newspaper complained that, “Butter and eggs are scarce articles in this market at present. The brethren seem not to be moved by revelation in the matter of the best time to come with those commodities, but generally occasion a feast or a famine.”37 At Pioche, the confrontation could be more direct. Armed bandits sometimes worked the roads leading from town where they attacked returning Mormon traders and stole their cash profits. On one occasion a thief even reportedly admonished his victim “to go and sin no more by dealing with Gentiles.” In response, the newspaper advised the LDS teamsters to “carry arms and be always ready to defend themselves.”38 Attacks of a different sort occasionally occurred in town. One day after Mormon Orson Huntsman had unloaded his lumber at the Raymond and Ely mine he asked the superintendent how long before the whistle would blow, explaining that the noise would spook his horses. The superintendent responded that it would not blow for another hour, but then promptly went in and “turned the whistle loose, loud as thunder.” Huntsman’s team and wagon bolted and did not stop until it crashed a quarter of a mile away.39

Mountain Meadows Massacre

Apart from these trading relationships, at least a part of the miners’ negative view of southern Utah Mormons was filtered through the dark lens of the Mountain Meadows Massacre. That massacre, although already over a decade old by the time Pioche and Silver Reef sprang to life, still colored the miners’ perception of Mormons in southwestern Utah. The massacre had occurred in 1857, a year in which war hysteria permeated Utah society. Brigham Young had declared martial law and the Mormons braced for an invasion of federal troops in what came to be called the Utah War. Within that context, zealous southern-Utah Mormons and Southern Paiute Indians reacted beyond the bounds of reason to murder all but the youngest members of the Baker-Fancher party, a California-bound immigrant group from Arkansas. The Mormon participants then took an oath of silence to conceal their roles in the tragedy, laying blame at the feet of the Southern Paiutes. The federal government successfully prosecuted only one Latter-day Saint, John D. Lee, for the crime. In 1877 officials took Lee back to the site of the massacre where a firing squad executed him.40

The massacre and its subsequent cover-up offered plenty of opportunity for miners at Pioche and Silver Reef to view their Mormon neighbors with a jaundiced eye. Blood from the slaughter soaked deeply into the southern-Utah soil but never deep enough to disappear altogether. Pioche developed its own connection to the massacre, which miners used to re-stain Mormonism with grisly proof of murder and conspiracy.

In 1871, Philip Klingensmith, Mormon bishop at Cedar City at the time of the massacre, became the first participant to break his oath of silence. He did so in a sworn affidavit before the county clerk at Pioche. On 27 September 1872, the Pioche Record ran the confession on its front page. In it residents not only learned gruesome details of the massacre, but read that Klingensmith feared for his life and believed that he would have been assassinated had he made the same confession before any court in the Territory of Utah. Following this disclosure, the Record carried succeeding reports of Mormon retaliatory threats against Klingensmith, including news of his rumored death in 1881 at the hands of Mormon “Destroying Angels.”41

The town’s other major connection to the massacre came through its “distinguished lawyer,” William W. Bishop, who served as John D. Lee’s attorney. Lee faced two trials, at the second of which an all Mormon jury found Lee guilty of murder and the judge sentenced him to die. Rumors circulated that Lee was offered up as a scapegoat to prevent prosecution of other higher ranking Latter-day Saints. As these events played out, the Pioche newspaper kept its readers informed of Bishop’s activities at the trials and hinted at a conspiracy following news of the verdict. Bishop himself claimed that he was used by the Mormon priesthood “when they had need for him” and “kicked by them” when “they had need to drop him.”42 The Pioche Record speculated about a conspiracy surrounding Lee’s execution and wondered “how large an amount Brigham Young paid to secure the execution of John D. Lee?”43

Reports from Silver Reef also hinted at a Mormon plot designed to shield Brigham Young and silence Lee. After Lee’s execution one account claimed that Young told St. George Mormons that “Lee’s residence and address is now in h-ll; that Lee did not go to h-ll on account of the little spree at Mountain Meadows, twenty years ago, but for telling lies about Brigham and the other boys.”44 Another story from Silver Reef suggested that Rachel Lee, one of John D. Lee’s widows sought vengeance against Brigham Young for turning his back on her husband. As the newspaper put it, on Young’s return trip to Salt Lake City in 1877, he was “guarded by three wives, two Apostles, and fourteen mounted men, armed with carbines.” “It is said that Rachel has taken to the mountains well fixed with pistols and rifles,” the story continued. “She swears that if she catches the ‘old sinner’ she will unsex him.”45 Clearly the massacre and its aftermath shaped the views of Pioche and Silver Reef miners toward their LDS neighbors.

Women and Polygamy

The final cultural gap that separated the miners from Mormons centered upon polygamy in general and Mormon women specifically. Southern Utah Mormons fretted over the potential loss of their women to the seductive gentile miners, while the miners viewed Mormon polygamy with scorn and Mormon women as would-be companions.

Perhaps in no other way was the contrast between the two societies more stark than in their familial lives. At Pioche in 1870 there were 1,248 men for every 100 women. Only forty-two families lived at Pioche that year, in a population that totaled over 1,100 people.46 At Silver Reef the story was similar. Out of a total population of 1,046 in 1880, 459 were single men, a full 45 percent. As historians Douglas D. Alder and Karl F. Brooks note, “There were more single men in Silver Reef than there were in the rest of the county combined.”47 Given these demographic disparities it is no wonder that women became a source of contention between the two cultures.

At Panaca, Mormon priesthood leaders did their best to guard against gentiles who invaded LDS church dances, whiskey in tow.48 Hebronites also held dances for town youth, which attracted outsiders. Bishop George Crosby set the standard for that town: He “wished the dances conducted with soberness & not kept to[o] late & not invite any profane rowdies that some times come from other places with the Spirit of Liquor which drives away the Spirit of the Lord.”49 To combat such occurrences, Hebron leaders appointed one of the elderly men to preside at the dances and keep outsiders away. In 1877 St. George leaders traveled to Hebron and emphasized this point. John D.T. McAllister, a regional church head, warned Hebronites “against mixing up with gentiles and partaking of their spirit for that is a plan of the Devil to lead people astray.” He also advised the congregation not to allow gentiles into their dances and gave “good advice” on courtship. He instructed Hebron men to “not be sparking 4 years and then not marry—but marry these girls and not let gentiles have them.”50

Despite warnings to the contrary, there were at least a few Mormon women who married miners. Emma Atchison, a Mormon from Panaca, married John H. Ely, a partner in the Raymond and Ely mine. The union proved influential in securing Mormon aid for Ely as he developed mines at Pioche and a mill at Bullionville.51 Romance brought another couple together too. A resident of Pioche evidently “fell in love with the Bishop’s daughter at Eagle Valley” and determined to marry her, but not before becoming a Mormon himself. The Pioche newspaper made light of the affair: “Another nice young man has been saved from everlasting damnation,” it announced. The youth went to St. George, and “was doused into the grease vat in the temple and wears endowment duds.” That was a consequence of loving a Mormon, “he either had to go through the vat or do without the girl. . . . That’s right, young sisters, make the boys get well greased before you marry them,” the paper jabbed.52

A report from Silver Reef suggested that at least some of this intermarrying was only an avenue used by miners to sleep with Mormon women over the winter never fully intending to remain married. It called the miners who did this, “Winter Mormons": “A Winter Mormon is generally an honest miner who drops into a Mormon village some cold Winter, is suddenly taken with a strong religious fever, gets baptized in a hurry, falls in love, gets married, and as soon as Spring sets in, he remembers that he has business elsewhere; accordingly steals a horse and disappears.”53 Those at Silver Reef seemed amused by these occurrences. One headline in the Silver Reef newspaper announced, “A Bishop’s Dream is Ended; His Intended Third Wife Elopes with a Wicked Gentile.”54 Another story suggested that such intermixing caused Mormon leaders at St. George to wring “their hands in holy horror.” Such Mormon concern offered all the more reason for those at Silver Reef to gloat: “Gentile boys and Mormon girls are getting fearfully mixed up. That’s right, boys and girls, do your duty. The population needs increasing.”55

Clearly polygamy was at the bottom of this contest over women, a fact that erupted into a political battle in southern Utah by 1882. A growing national outrage over Mormon marital practices prompted Congress to pass the Edmunds Act early that year. This law made it easier to convict polygamists by lowering the standard of proof. No longer would lawmen have to provide evidence of illegal marriage, they would simply have to prove “unlawful cohabitation.” It also disqualified polygamists from voting, serving on juries, and holding public office.56

As Congress debated the Edmunds bill, the Pioche Record weighed in on the issue in a lengthy editorial titled “Down with Polygamy.” The paper actually began its argument in a somewhat sympathetic tone toward its polygamous neighbors, especially as it pointed out the hypocrisy of many easterners who denounced Mormons as immoral, yet indulged in extramarital affairs themselves. Still, the paper’s stance was decidedly anti-polygamy, albeit with a sarcastic twist: “The people of Southeast Nevada have done more to blot out the practice of polygamy among the Mormons than all the balance of the inhabitants of the American continent combined,” the Record bragged. Its method of “throttling this twin relic of barbarism” was simply for the miners to marry “the Utah girls” themselves. When a Mormon wed more wives than the law allowed, “the Navadians have eloped with the extra wives,” the paper explained. “The Mormons must be taught that they have to cease the practice of polygamy,” it wryly demanded, “even if every man in Lincoln county has to marry two dozen wives himself. Down with polygamy.”57

The sentiment at Silver Reef was similar. Following the passage of the Edmunds Act, the front page of the Silver Reef newspaper announced, “Passed! The ‘Twin-Relic’ Doomed by the Voice of the Nation. Polygamy to the Rear and America to the Front.” Another day it gloated, “The funeral of polygamy will soon begin. No postponement on account of the weather;” and, in a more light hearted column, the Silver Reef Miner took a jab at the LDS Church owned Deseret News which had recently defended polygamy as more honorable than monogamy. The Miner replied, “If the editor of the Deseret News thinks that he can march into the golden [hereafter?] ultimately with a female college for a wife, and leave us outside hanging on the corner of a cloud with one ear, because we are a monogamist, he will get comparatively left.” More sarcastic, the newspaper concluded, “while the choir sings something mellow and soothing, will those who desire to be sealed please step forward and help us stamp out the vile heresy of monogamy?”58

Only a few months following these editorials Panaca saints made a friendly gesture toward their neighbors at Pioche and Bullionville in what turned out to be a public relations ploy on polygamy. The Mormons invited the miners to Sunday services to hear John D. T. McAllister, a regional church leader from St. George, address the group. Residents from Pioche and Bullionville responded enthusiastically as several buggy teams full of visitors filled the Mormon chapel. McAllister used the occasion to explain the practice of polygamy to the outsiders—but to little avail. The editor of the Record joked that the truthfulness of the discourse caused the visitors to look “upon the seven beautiful young ladies who composed the choir” and to conclude “how happy we would be with all of them, and yet how miserable with only one.” This dig aside, the editor complimented McAllister’s preaching and noted that, “owing to the number of gentiles present, . . . those who spoke were all very careful not to utter a word which would offend any one in the house. . . . We were well satisfied with our trip to Panaca.”59

By the end of 1882 the rift over the Edmunds Act had grown to politically polarize Washington County and to energize the state’s two political camps, the Liberal Party, or the non-Mormon party, and the People’s Party or the Mormon party. On October 3, a group of concerned residents gathered at the Citizens Hall in Silver Reef and effected a permanent organization of the Liberal Party in Washington County. As Silver Reef residents viewed it, “There are but two political parties in this Territory: the Liberal party, composed of the law-abiding, liberty-loving, progressive class; and the People’s party, composed of the blind dupes of a fanatical Priesthood.” As a result the “Liberal voters of Washington County, in mass Convention assembled,” resolved to “pledge our best efforts towards the Political overthrow of the disloyal element that demoralize our industries, impede our progress and brings shame and dishonor upon this otherwise favored Territory.” They also resolved to “invite to our ranks Young Utah, and remind them that shame, disgrace and a nation’s scorn is their lot if they continue to bow to priestly dictation.” They ended with a marked opposition “to priestly rule in Utah” and a demand for “the separation of Church and State.” The meeting adjourned amidst “three hearty cheers for the Liberal party.”60

In response, two weeks later, at seven o'clock p.m., another group of concerned citizens, this time Mormons, gathered outside the courthouse at St. George “amid display of fire works and firing of salutes.” Led by the Martial Band playing lively music, the group marched the two blocks from the courthouse to the Tabernacle, clutching lighted torches the entire way. Once at the Tabernacle, Thomas Judd, an influential local Mormon business leader called to order a mass meeting of the People’s Party of St. George. A. R. Whitehead initially addressed the crowd and set the tone for the remainder of the meeting. He told those gathered that night that there were “two Political Parties in Utah,—The People’s Party, composed of the lovers of Justice and Constitutional Rights; the other, the Liberal Party, composed of a few men headed by unprincipled ‘office seekers.’” Before departing the crowd adopted unanimously and “amid great applause” a series of resolutions, including a pledge to “resist, by every lawful means in our power, the unconstitutional and despotic measures sought to be forced upon us by our enemies in their attempts to gain possession of our substance and to enrich themselves from the spoils.”61

Changing Attitudes, 1880s and 1890s

Polygamy continued to polarize Southern Utah politically and socially until the Mormons finally abandoned the practice in 1890, laying the groundwork for statehood six years later. On the event of Utah Statehood, the Pioche newspaper devoted nearly two columns to its coverage, under the headline, “Now the State of Utah.” By that time the Mormons had renounced polygamy, adopted the national two party political system, and local saints were embracing mining. To gain statehood Mormons had abandoned the key principles—polygamy and theocracy—that divided them from the miners at Pioche and Silver Reef and the rest of the nation. Those gone, it was easy for Pioche to welcome Utah into the sisterhood of states. Although the newspaper did not comment on the event, it ran a wire from the Washington press which noted, “The Mormon question was at one time thought to interpose insuperable obstacles to Statehood; but with the downfall of polygamy Mormonism has ceased to be viewed as a menace to the institutions of the land.”62

By the end of the nineteenth century Mormon attitudes towards mining also brought them more in line with prevailing norms. This process began at Young’s death in 1877, which marked an easing of restrictions. Young’s successor, John Taylor, was less committed to communalism and more open to capitalism and business.63 Mormon economic interaction at Pioche, Silver Reef, and newer mining camps continued well past the turn of the century, with little fear that such activity would be made a matter of LDS church fellowship. At Silver Reef Mormons even entered the workforce as miners, especially following the town’s unionization effort and failed strike.64

Interaction at Mormon dances at Panaca in the 1880s perhaps still posed a problem, but the Pioche newspaper suggested “lozenges” to aid in courtship of the Mormon girls. It also noted that “the Bullionville store does a large business alone from the sale of fancy toilet articles, as it takes a bottle of scent to make the average young Bullionite presentable to his Panaca sweetheart.” It further warned “all Gentiles” attending Mormon dances “not to press the young ladies too closely to their manly bosoms, for it is against the rules of the Church.” Nonetheless, by 1900 the earlier need to protect Mormon women from outsiders had all but vanished. That year the Young Ladies Mutual Improvement Association at Panaca threw a “grand ball” and extended “a cordial invitation to Piochers to come and join in their amusement.” In response, the Pioche Record observed that “a number of our young folks are arranging to go down.”65

Likewise, when DeLamar burst onto the mining scene in the 1890s, Mormons hardly thought twice about participating. In 1894 prospectors founded a town about forty miles southwest of Pioche and named it DeLamar, after a prominent investor.66 By 1896 reports in the St. George newspaper detailed activity at the mines; one account from DeLamar noted that “most of the men that are working here are from Utah.”67 News from Panaca described “some little excitement” over “gold and silver prospects,” with no hint at disapproval of Mormon participation in such activities.68 Another report even bragged that “a new strike has just been made by Spring Valley boys, on the Utah and Nevada line.” The writer, a Panaca Mormon, proudly announced that “some of Panaca’s sons have a six months lease on a fraction of the main ledge, and expect to pull out with a neat sum.”69 Thus, by the turn of the century frontier saints had not only made peace with the region’s mineral wealth, but sought it for themselves.70

Cross Cultural Understanding

Clearly, a vast cultural divide separated the Mormons and miners in nineteenth-century southern Utah. Sadly, peoples from both groups made little effort to look past their differences to find commonalities. The few attempts Mormons and miners made to do so stand out because they were so rare. Perhaps the best know case of intercultural mingling took place in this tabernacle in 1879, an interdenominational mass orchestrated by Father Lawrence Scanlan of the Catholic Church and John Macfarlane, a Mormon surveyor and musician. Macfarlane arranged for a Mormon choir to sing songs for a High Mass in Latin and secured use of the tabernacle for the event. Scanlan then conducted the service to the approval of the Catholic faithful and a throng of curious Mormon onlookers.71

Franklin Buck, a businessman and investor in mines at Pioche should also be remembered for his effort to develop relationships of understanding. In 1871 Franklin Buck visited among the Saints at several southern Utah towns. Upon his return to Pioche he concluded that “the Mormons are the Christians and we are the Heathens.” He went on to compare Pioche with what he found at the Mormon towns: “In Pioche we have two courts, any number of sheriffs and police officers and a jail to force people to do what is right. There is a fight every day and a man killed about every week. About half the town is whisky shops and houses of ill fame. In these Mormon towns there are no courts, no prisons, no saloons, no bad women; but there is a large brick Church and they keep the Sabbath—a fine schoolhouse and all the children go to school. All difficulties between each other are settled by the Elders and the Bishop. Instead of every man trying to hang his neighbor, they all pull together. There is only one store on the co-operative plan and all own shares and it is really wonderful to see what fine towns and the wealth they have in this barren country. It shows what industry and economy will do when all work together.” “The Devil is not as black as he is painted,” Buck concluded.72

Lessons

Exploring the cultural gulf that tended to isolate the Mormons and silver miners behind walls of intolerance can teach important lessons not only about life in nineteenth century southern Utah, but about the nation as a whole. At its most basic level, the struggle between Mormons and miners in Utah’s Dixie is a frontier story about what it meant to be an American during the last half of the nineteenth century. Miners at Silver Reef and Pioche embodied American progress, individualism, acquisitiveness, and destiny. To the miners at Pioche and Silver Reef, Mormon polygamy and theocracy fell outside prevailing standards of Americanness. As Mormons abandoned polygamy and theocracy the walls of separation diminished and even miners at Pioche were willing to welcome their Mormon neighbors into the sisterhood of states. In essence, then, the Mormons and miners, through their forty-year struggle to coexist had planted a portion of America’s national identity into the desert soil of Utah’s Dixie.

On a local level, too, there are important lessons. The cultural gap separating Mormons and miners illustrates fundamental issues governing the human condition. What does it mean to be a good neighbor, especially to peoples with drastically different values than yours? Is it possible to look past cultural diversity to view broader commonalities? The Mormons and silver miners who inhabited Utah’s Dixie struggled to answer those questions for themselves. For the most part members of both groups looked across the cultural gap and described the peoples they saw there in disparaging ways. Mormons and miners both tended to create caricatures of each other that exaggerated each group’s undesirable features. Mormons looked at Pioche and Silver Reef and described the miners that they saw there as wicked-unprincipled-ungodly-evil-gentile minions who were at work in the devil’s kingdom. Similarly the miners viewed the Mormons as uncivilized-barbarous-fanatical-polygamous murderers, who were blind dupes to priestly rule. Peoples from both groups generally spent little time looking past differences to find commonalities that might have been used to bring them together for the common good. They also failed to recognize how interdependent their lives had become. It was easy, in other words, for Mormons and miners to belittle each other from across deep cultural divides, but when they took time to develop relationships, perceptions generally changed.

In the end, history’s lessons are only valuable if we search for ways to apply them. In that regard, nineteenth-century Dixie Mormons and miners might also open our eyes to the injustice of stereotyping and may prompt us to view southern Utah’s much more diverse population of the twenty-first century with a measured sense of mutual understanding. Unfortunately, a recent letter to the editor in the Spectrum sounded like an echo from the past. It made me wonder if, rather than Mormons and miners, new lines are being drawn along a Mormon/Californian divide? The letter writer, a relative newcomer to Utah’s Dixie, complained that upon her arrival she was greeted somewhat derisively with “‘Oh! Another Californian.’” In response she described “people of the Latter-day Saint faith” as “shallow” with a proclivity to “think they are better than others.” She admonished those “of the LDS faith” to “get a grip.”73

As residents of Utah’s Dixie enter the twenty-first century living in Utah’s fastest growing county, they may do well to recall Franklin Buck’s conclusion after taking the time to get to know his neighbors: “the Devil is not as black as he is painted”—Mormons and Californians rarely are either.74

Works Cited

1. Considerable portions of this lecture are gleaned from my book, W. Paul Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier: Mormons, Miners, and Southern Paiutes (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2007), chapters five and six. Additional research allowed me to add the perspective of Silver Reef, which is not found in the book. As I argue in the book, during the nineteenth-century there were at least three competing world views that came into conflict in southern Utah and which jostled for power, that of the Mormons, silver miners, and Southern Paiutes. For the purposes of the Brooks lecture I have chosen to focus upon the chasm separating the Mormons and miners and I refer you to Making Space on the Western Frontier for the added perspective of the Southern Paiutes.

2. Erastus Snow, St. George, to Brigham Young, Salt Lake City, Journal History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (chronology of typed entries and newspaper clippings, 1830 to the present), 22 July 1869, 1-2 (hereafter cited as Journal History), Family and Church History Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

3. Heber C. Kimball, 19 February 1865, Journal of Discourses, 26 vols. (London and Liverpool: LDS Booksellers Depot, 1855-86), 11: 82.

4. For a more complete exploration of these two competing ideals see Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier, chapters two, three, five, and six.

5. James G. Bleak to Erastus Snow, Journal History, 2 April 1866, 8-9; James G. Bleak, “Annals of the Southern Utah Mission,” typescript, vol. A, 223-24, Special Collections, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

6. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. A, 309.

7. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 23.

8. Snow to Young, Journal History, 22 July 1869, 2.

9. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 146.

10. Journal History, 5 June 1870, 6.

11. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. A, 196-7.

12. Hebron Ward Historical Record, vol. 2 (1867-72), 42, microfilm, Historical Department, Church Archives, Family and Church History Department, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City. The following year local leaders instructed the Hebron congregation “to cease trading with and sustaining gentiles—don’t run after the mining or rail roads, but stick to the farms and business at home and you will be richer and have more of the spirit of the gospel.” (vol. 2, 63).

13. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 132-35.

14. James W. Hulse, Lincoln County, Nevada, 1864-1909: History of a Mining Region (Reno: University of Nevada Press, 1971), 22-3, 28; Michael Bourne, “Early Mining in Southwestern Utah and Southeastern Nevada, 1864-1873: The Meadow Valley, Pahranagat, and Pioche Mining Rushes” (Master’s thesis, University of Utah, 1973), 114. Washington County’s 1870 population totaled 3,064, while by 1880 it had grown to 4,235. See Allan Kent Powell, “Population,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allan Kent Powell (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1994), 432.

15. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 173-75, 179-82; Hebron Ward Historical Record, vol. 3 (1872-97), 14, holograph photocopy, Enterprise Branch, Washington County Library, Enterprise, Utah. For an analysis of the type of strain such trade likely placed on the Utah economy see Dean L. May, Three Frontiers: Family, Land, and Society in the American West, 1850-1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 173, especially note 55.

16. Brigham Young, 1 January 1877, Journal of Discourses, vol. 18 (London: LDS Booksellers Depot, 1877), 305. Young further warned southern-Utah men against “putting their wives and daughters into their [gentile] society.”

17. After citing Erastus Snow’s 1865 order to cut off “any man that would go to the western mines as a miner,” historian Leonard Arrington argues that “there are no discoverable instances of such excommunications.” (Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints, 1830-1900 (1958; reprint, Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 474 note 42). Close scrutiny of local records indicates otherwise. See Reeve, Making Space on the Western Frontier, 94-95, for additional examples.

18. Hebron Ward Historical Record, vol. 2, 36, 44; Rio Virgen Times, (St. George, Utah), 12 May 1869.

19. Daily Union Vedette, 31 January 1866.

20. Pioche Daily Record, 28 March, 24 April 1873.

21. Rossiter W. Raymond, Statistics of Mines and Mining in the States and Territories West of the Rocky Mountains, U.S. Treasury Department, annual report, (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873), 300; George M. Wheeler and Daniel W. Lockwood, Preliminary Report upon a Reconnaissance through Southern and Southeastern Nevada, Made in 1869, U.S. Army Engineer Department (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1875), 54; U.S. House, 39th Congress, 1st Session, Committee on the Territories, The Condition of Utah, House report No. 96, serial set 1272, 13.

22. “‘Brigham’ at St. George,” Pioche Tri-Weekly Record, 24 November 1876.

23. “Southern Utah,” Salt Lake Tribune, 2 May 1876.

24. “Southern Utah,” Salt Lake Tribune, 19 December 1875.

25. “Hurrah for Leeds!,” Salt Lake Tribune, 22 November 1876.

26. See, W. Paul Reeve, “Silver Reef and Southwestern Utah’s Shifting Frontier,” in From the Ground Up: The History of Mining in Utah, ed. Colleen Whitley (Logan: Utah State University Press, 2006), 250-71 for an assessment of Silver Reef’s economic impact upon southern Utah. See also Alfred Bleak Stucki, “A Historical Study of Silver Reef: Southern Utah Mining Town” (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 1966), 104-6; Douglas D. Alder and Karl F. Brooks, A History of Washington County: From Isolation to Destination (Salt Lake City: Utah State Historical Society and Washington County Commission, 1996), 114-15.

27. Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 106-8.

28. Andrew Karl Larson, “I Was Called To Dixie,” the Virgin River Basin: Unique Experiences in Mormon Pioneering (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1961), 262-65; Alder and Brooks, A History of Washington County, 111.

29. Brigham Young, Salt Lake City, to Erastus Snow, St. George, 7 June 1871, in Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 109-13, 127; Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah, vol. 4 (Salt Lake City: George Q. Cannon, 1904), 275; Journal History, 23 October 1871, 4.

30. Journal History, 25 November 1872, 1.

31. Orson Welcomes Huntsman, Diary of Orson W. Huntsman, typescript, vol. I, 53-4, L. Tom Perry Special Collections Library, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, Utah.

32. For examples of Huntsman’s work at Pioche and Bullionville, see ibid., vol. I, 74, 81, 82, 94, 96, 110, 111.

33. Ibid., vol. I, 94.

34. Hebron Ward Historical Record, vol. 3, 22.

35. Pioche Daily Record, 30 March; 18, 19, 30 April 1873; 7 April 1877. For additional reports of trade goods from Utah see Pioche Daily Record, 21, 26 September 1872; 8 February; 23 March; 2, 11, 12, 13, 30 April 1873; 16 January 1874; 1 August 1876; 25 August 1877; 28 June 1884; Jack R. Mathews, “Mule Skinners and Bull Whackers: An Archeological Study of Two Historic Wagon Roads in Southeast Nevada” (Master’s thesis, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, 1992), 35-7; and William R. Palmer, “Early Day Trading with the Nevada Mining Camps,” Utah Historical Quarterly 26 (October 1958): 353-68.

36. Mathews and Palmer chronicle Mormon trade at Pioche past the turn of the century. Mathews, “Mule Skinners;” Palmer, “Early Day Trading.” Mathews documents other avenues of supply for Pioche, from San Francisco, Salt Lake City, and the East (25-34).

37. “Brieflets,” Silver Reef Miner, 7 October 1882; 27 August 1881.

38. Pioche Daily Record, 21 September 1872; Pioche Weekly Record, 25 August 1877; Mathews, “Mule Skinners,” 44; Palmer, “Early Day Trading,” 356; Huntsman, Diary, vol. I, 94.

39. Mathews, “Mule Skinners,” 44; Huntsman, Diary, vol. 2, 33. See also Pioche Daily Record, 13 April 1873.

40. On the Utah War see Norman F. Furniss, The Mormon Conflict, 1850-59 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1960); Donald R. Moorman and Gene A. Sessions, Camp Floyd and the Mormons: The Utah War (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1992); Richard D. Poll and William P. MacKinnon, “Causes of the Utah War Reconsidered,” Journal of Mormon History 20 (Fall 1994): 16-44; William P. MacKinnon, “The Buchanan Spoils System and the Utah Expedition: Careers of W. M. F. Magraw and John M. Hockaday,” Utah Historical Quarterly 31 (spring 1963): 127-50. On the Mountain Meadow Massacre see Juanita Brooks, The Mountain Meadows Massacre, (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1962); Idem, John Doyle Lee: Zealot, Pioneer Builder, Scapegoat, 3rd ed. (Salt Lake City: Howe Brothers, 1984); and Will Bagley, Blood of the Prophets: Brigham Young and the Massacre at Mountain Meadows (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2002).

41. Pioche Daily Record, 27 September; 5, 8 October 1872; Pioche Weekly Record, 23 July 1881; Anna Jean Backus, Mountain Meadows Witness: The Life and Times of Bishop Philip Klingensmith (Spokane, Washington: Arthur H. Clark Company, 1996), 217-22, 231.

42. Pioche Daily Record, 25 May, 23 July, 1 August 1875; 29, 30 September 1876; Brooks, Mountain Meadows Massacre, 191-98.

43. Pioche Weekly Record, 5 May 1877.

44. “From Silver Reef,” Pioche Weekly Record, 7 April 1877.

45. “From Silver Reef,” Pioche Weekly Record, 5 May 1877.

46. Hulse, Lincoln County, 22; Bourne, “Early Mining,” 142-143; Carolyn Grattan-Aiello, “The Chinese Community of Pioche, 1870-1900,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 39 (Fall 1996): 201-15.

47. Paul Dean Proctor and Morris A. Shirts, Silver Sinners and Saints: A History of Old Silver Reef, Utah (N.p.: Paulmar, 1991), 113-19; Alder and Brooks, A History of Washington County, 86; Nels Anderson, Desert Saints: The Mormon Frontier in Utah (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1942), 428-32. The demographic information on Silver Reef is taken from the above sources as summarized in Reeve, “Silver Reef” in From the Ground Up, ed. Whitley, 265.

48. Leonard J. Arrington and Richard Jensen, “Panaca: Mormon Outpost among the Mining Camps,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 18 (Winter 1975): 214.

49. Hebron Ward Historical Record, vol. 3, 69.

50. Ibid., vol. 3, 108-9; for similar advice given at St. George in 1873, where one speaker “alluded to the influence of strangers over our unsuspecting females,” see Bleak, “Annals,” vol. B, 185.

51. Bourne, “Early Mining,” 68-9; James W. Abbott, “The Story of Pioche,” in The Arrowhead: A Monthly Magazine of Western Travel and Development (Los Angeles: San Pedro, Los Angeles, and Salt Lake Railroad, 1907), 6; Hulse, Lincoln County, 18-19; Charles Gracey, “Early Days in Lincoln County,” in First Biennial Report of the Nevada Historical Society, 1907-1908 (Carson City, Nevada: State Printing Office, 1909), 108; White Pine Daily News (Hamilton/Treasure City, Nevada), 28 July 1870; John L. Considine, “The Birth of Old Pioche,” Sunset: The Pacific Monthly 54 (January 1925): 29.

52. Pioche Weekly Record, 28 June 1884; 2 June 1883.

53. “From Silver Reef,” Pioche Weekly Record, 5 May 1877.

54. Silver Reef Miner, 16 July 1881.

55. “Silver Reef News,” Pioche Weekly Record, 20 November 1880; “Silver Reef News,” Pioche Weekly Record, 15 January 1881.

56. Edward Leo Lyman, Political Deliverance: The Mormon Quest for Utah Statehood (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 22-3. Congress further decided to apply the Edmunds Act, ex post facto, to block Mormon polygamist George Q. Cannon from continuing to serve as Utah’s territorial delegate to Congress. The two political rallies described here met in response to a need to elect a new territorial delegate. The Liberal Party at Silver Reef nominated Allen G. Campbell, a Utah mine owner, and the People’s Party, John T. Caine, a monogamist Mormon. Campbell did not garner the Liberal Party nomination for Utah Territory as a whole. Regardless, Caine won the election. See coverage in Silver Reef Miner, 7, 21, 28 October, 4 November 1882. For broader context on Cannon’s removal from office see Davis Bitton, George Q. Cannon: A Biography (Salt Lake City, Utah: Deseret Book Company, 1999), chapter seven.

57. Pioche Weekly Record, 25 February 1882.

58. For reaction at Silver Reef to the Edmunds Act see Silver Reef Miner, 15, 17, 24 March 1882.

59. Pioche Weekly Record, 13 May 1882.

60. “Minutes of a Liberal Convention,” Silver Reef Miner, 7 October 1882.

61. “Minutes of a Mass Meeting of the People’s Party,” Silver Reef Miner, 21 October 1882.

62. Pioche Weekly Record, 9 January 1896.

63. John Taylor made positive statements about mining, and he, along with other LDS church leaders such as Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F. Smith, invested in silver and gold mines in the 1880s and 1890s. This, however, did not ease the “problems of conscience” that some Mormon miners experienced. See Leonard J. Arrington and Edward Leo Lyman, “The Mormon Church and Nevada Gold Mines,” Nevada Historical Society Quarterly 41 (Fall 1998): 191-205; Philip F. Notarianni, “Mining,” in Utah History Encyclopedia, ed. Allan Kent Powell, 367; Donald Q. Cannon, “Angus M. Cannon: Frustrated Mormon Miner,” Utah Historical Quarterly 57 (Winter 1989): 36-45.

64. See Reeve, “Silver Reef” in From the Ground Up, ed. Whitley, 268-70.

65. Pioche Weekly Record, 23 July 1881; 4 February 1882; 8 February 1900.

66. For detail on DeLamar see Hulse, Lincoln County, chapter 6.

67. St. George Union, 22 February 1896.

68. St. George Union, 12 March 1896.

69. St. George Union, 25 January 1896. For other favorable reports at St. George regarding mining activity at DeLamar see St. George Union, 16 April, 21 May 1896; and 27 February 1897. For other evidence of Mormon prospecting around the turn of the twentieth century, see Carrie Elizabeth Laub Hunt, Memories of the Past and Family History, (Salt Lake City: Utah Printing Co., 1968), 47.

70. In the 1890s, the LDS church itself even looked to Nevada’s mineral wealth as a potential solution to its financial difficulties. The church’s first presidency, consisting of President Wilford Woodruff, George Q. Cannon, and Joseph F. Smith, all sat on the board of directors of the Sterling Mining and Milling Company which owned mines in Nye County, Nevada, immediately west of Lincoln County. See Arrington and Lyman, “The Mormon Church and Nevada Gold Mines.”

71. See Reeve, “Silver Reef,” in From the Ground Up, ed. Whitley, 266-67; W. Paul Reeve, “In 1879 a Mormon Choir Sang for a Catholic Mass in St. George,” The History Blazer, March 1995; Alder and Brooks, History of Washington County, 115-16; Stucki, “Historical Study of Silver Reef,” 47-48; Francis J. Weber, “Catholicism among the Mormons, 1875-79,” Utah Historical Quarterly 44 (Spring 1976): 141-48; Robert J. Dwyer, “Pioneer Bishop: Lawrence Scanlan, 1843-1915,” Utah Historical Quarterly 20 (April 1952): 135-58. For an account of a 2004 reenactment of the 1879 event see Nancy Perkins, “Religious Friends Relive Historic Moment,” LDS Church News, 22 May 2004, 5.

72. Franklin A. Buck, A Yankee Trader in the Gold Rush: The Letters of Franklin A. Buck, comp. Katherine A. White (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1930), 234-36.

73. Leanette Robertson, “Not made to feel welcome in Dixie,” The Spectrum, 28 December 2006, A6.

74. For evidence of Washington County’s growing religious diversity see Alder and Brooks, A History of Washington County, 294-98; and Matt Canham, “Mormons in the Mix: Washington County population boom religiously diverse,” Salt Lake Tribune, 26 July 2005.